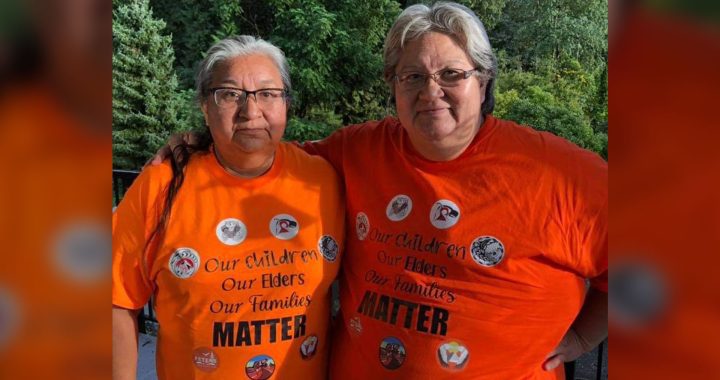

Residential school survivor Betsy Bruyere (left) marches in this undated photo. Photo: Facebook

Warning: This story has disturbing details about Indian residential schools. If you are feeling triggered, the National Indian Residential School Crisis Hotline can be reached at 1-866-925-4419.

Finding the remains of 215 children is another sorry chapter in the history of Canada’s Indian residential schools, former students say.

“We suspected this for some time,” said Betsy Bruyere of Vancouver who prefers to be called a survivor.

“It was a very emotional weekend.”

The Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc Nation, near Kamloops, B.C., announced May 27 it discovered unmarked graves at the site of the old Kamloops Indian Residential School.

The school, operated by the Roman Catholic church between 1890 and 1969, was the largest in the residential system with as many as 500 students at a time.

READ MORE:

Remains of 215 children found at former residential school in British Columbia

The childrens’ remains were detected over the Victoria Day long weekend using a ground-penetrating radar, the band said in a news release.

Bruyere, who grew up on Sagkeeng First Nation in Manitoba, was one of an estimated 150,000 First Nation, Métis and Inuit students forced to attend 139 schools across Canada that operated to assimilate Indigenous children for more than 100 years.

The last one closed in 1998.

Much has been written about the schools’ notorious and abusive reputations, but it’s only in the past decade that survivors have been heard thanks to the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement and its Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

“I was sent there under protest,” said Bruyere of her time at Fort Alexander Residential School. “(The priest) came knocking at the door and he harassed my mother for a long time to put me in residential school.

“Finally she gave in when he said he was going to call the cops. I was six, and I was confined for seven years.”

Bruyere suffered physical and sexual abuse, which left an indelible mark on her life.

She said it took years to be believed, supported and treated.

That includes her stories of children who never came home.

“It was just like getting stabbed in the heart,” she said of hearing about the mass grave in Kamloops on the news.

The official record reflects only 50 deaths at that Kamloops school.

Also grieving the dead is Garnet Angeconeb of Sioux Lookout, Ont.

“What’s happened in Kamloops really is a validation of the things that we – as survivors – have been saying for many, many years,” he said.

Angeconeb, originally of nearby Lac Seul First Nation, went to Pelican Lake Residential School and has spent his life advocating for survivors and their need for ongoing counselling.

He feels the Kamloops discovery has served up the moral of the story like no other development.

“Sadly, it took the findings of these remains to wake up the nation,” he said, noting he is steeling himself for more undocumented graves to be announced.

Tony Stevenson, a survivor who shares his painful story with students in today’s mainstream classrooms, said the discovery is a validation.

“It has taken something like this for the federal government and the country to sort of wake up,” he said from Regina.

Stevenson attended the Qu’appelle Indian Residential School in Lebret, Sask., for 10 years, which has the distinction of being the last residential school to close its doors in Canada.

He believes education is the key to reconciliation with non-Indigenous Canadians.

“I now go to classrooms and anywhere else to teach that history and combat racism,” he said.

“When you hear people say, ‘Well, get over it’, I wish that they had a chance to hear survivors describing the life that they had to live.”

Many survivors, like Jason Nakogee’s mother, have died without learning about the shocking discovery in Kamloops.

Jacqueline Wesley was forced to attend St. Anne’s Residential School in northeastern Ontario, where survivors recount being shocked by the use of an electric chair.

The Kamloops gravesite has him reflecting on life with his mother in Attawapiskat First Nation.

“She was taken away,” said Nakogee, who now lives in Sudbury.

“My son is five right now and in the past they would have taken him too.”