Millions of dollars are spent every year to fight suicide epidemics amongst Indigenous peoples in Canada but the federal government collects little to no data about the actual suicide rates.

There is a serious lack of record keeping by all levels of governments and coroners’ offices when it comes to suicide deaths of Indigenous people, APTN Investigates has confirmed by requesting data from each province.

Cindy Blackstock, the executive director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada, said she is troubled the federal government isn’t tracking suicide data.

“I’m disappointed that we’re still not at a place where we’re keeping track of the number of attempts and deaths by suicide,” said Blackstock. She is calling for putting a rigorous system in place to better understand and fund the prevention of the suicide epidemic.

‘No First Nations suicide surveillance system’

Outbreaks of suicide deaths in Indigenous communities occur three times higher than the general public. Youth lose their lives to suicide at a rate five to six times higher than non-Indigenous youth in the country.

In some Indigenous communities, suicide has become a constant struggle, frequently forcing Indigenous leaders to declare a state of emergency. Remote Ontario First Nation declares state of emergency, calls for Canadian Rangers to help.

“Incidences of suicides are recorded in provincial/territorial vital events databases as a jurisdictional responsibility,” Health Canada stated in an email when asked how Indigenous suicides are tracked. The email added there is “no simple mechanism to identify First Nations within these provincial/territorial databases and there is no First Nations suicide surveillance system.”

APTN Investigates also filed an access-to-information request with the department of Indigenous Services Canada to ask the same query and was told “no records were located.”

“The answer is, ‘no data, no problem’, so you don’t have any data to back something up [and] then there’s ‘no issue,’” said Dr. Mike Kirlew, a Sioux Lookout Ont. based family doctor, who added he is baffled by the lack of data collected by both level of governments.

“That is extremely important data, to be able to say whether or not suicide rates are going up or down… so you can target your health intervention to make the biggest effect.”

One promising lead for data came from the Canadian Vital Statistics Death Database, which is an administrative survey that collects demographic and medical cause-of-death information annually from all provincial and territorial vital statistics registries on all deaths in Canada, according to Statistics Canada.

However, they do not track information by Indigenous identity. According to a recent standing committee on Indigenous and Northern Affairs report called, Breaking Point: The Suicide Crisis in Indigenous Communities, suicide rates may be underrepresented due to variations in reporting practices. For instance, some deaths may be reported as accidents rather than suicides. In addition, ethnicity is not reported on death certificates.

Bulk of provinces, organizations not keeping track of suicides

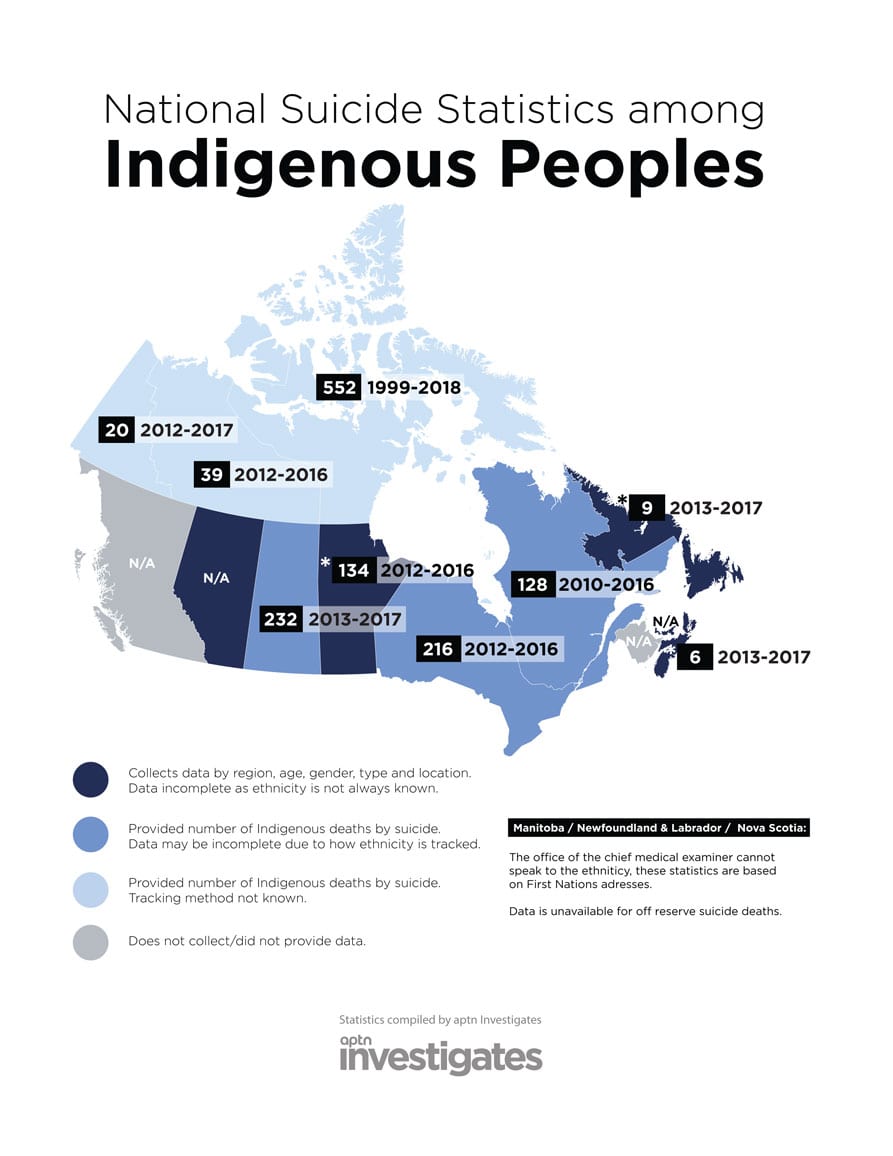

APTN Investigates contacted all provincial and territorial governments and several coroner’s offices to ask for data regarding the number of suicide deaths to do with Indigenous people over a five-year period. In some cases, we were referred back to Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada and Health Canada or told to contact individual First Nation communities.

Data compiled by APTN Investigates (story continued below):

Jarvis Googoo, the director of health at the Atlantic Policy Congress of First Nations Chiefs Secretariat (APCFNCS) was taken by surprise after learning the province of New Brunswick does not track these deaths.

“I was hoping New Brunswick was keeping track, given [the province] has a large number of First Nations communities in the province,” said Googoo. “It’s a disservice to First Nations people when suicide data is not being tracked because with proper numbers and with proper data, it could lead to long-term solutions to suicide prevention.”

Googoo said APCFNCS does not collect data either. APTN Investigates also contacted the Assembly of First Nations to ask if they kept track of these deaths. A spokesperson said they do not. The province of Alberta is another province that does not collect suicide data on Indigenous people, despite there being a crisis in many communities. Instead, the province collects suicide data by region not Indigenous identity.

“I’m not shocked at all because they just started to keep track of data to do with missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls,” said Katherine Swampy, a Samson Cree Nation band councillor.

Samson Cree Nation is one of four Indigenous communities that make up Maskwacis an hour’s drive south of Edmonton. The First Nation community has dealt with a rash of suicides earlier this year, prompting calls for a state of emergency.

Millions poured into mental health, suicide prevention

Even though Health Canada does not collect data regarding the number of suicides of Indigenous people, the department allocates millions of dollars each year to address the problem. The First Nation and Inuit Health Branch (FNIHB), has spent $619.8 million for mental health and suicide prevention between 2015-16 and 2016-17, with $358.8 million allocated for 2017-18. These funds are given to mental health programs such as the National Aboriginal Suicide Prevention Strategy, the Indian Residential School Resolution Health Support Program, the First Nations and Inuit Hope for Wellness Help Line and for Mental Wellness Teams.

Mental health services are also available through Jordan’s Principle funds and the Non-Insured Health Benefit Mental Health Counselling Benefit. Jordan’s Principle is a child-first principle that applies equally to all Indigenous children despite their location of residence. The province of Ontario had the highest total of expenditures for mental health services from 2008-2009 to 2016-2017, sitting at $521 million. The prairie regions are the second highest.

Georgina Jolibois, the NDP MP critic for Indigenous Services, said she is concerned about the way programs are delivered for Indigenous people.

“I still see bands across Canada do not get specific programming to deal with mental health and suicide and the grief and the trauma and other related issues,” said Jolibois. “The approach by the federal government is inefficient and ineffective for bands across Canada.”

They don’t because it is probably still their policy that we be eliminated, even to be forced over the cliff.

They don’t because it is probably still their policy that we be eliminated, even to be forced over the cliff.