Daniel took off his shirt to show APTN the deformity on his back. Photo by Cullen Crozier.

A First Nations youth is trying to remove himself from the care of northwestern Ontario child welfare agency so he can get the medical help he needs to address a rare treatable deformity that has worsened considerably under the agency’s watch.

The youth, and his prominent Toronto lawyer, have been asking Weechi-it-te-win Family Services in Fort Frances, Ont. to hand over his customary care agreement.

Weechi did not respond to the first request in June.

Or the second request made on Oct. 21.

A third attempt made three days ago has likewise not received an answer.

It was made by John Kingman Phillips, a partner with Waddell Phillips Inc.

“If no customary care agreement is provided, or confirmed not to be in place, I demand to know on what legal basis your organization purports to have been dealing with (the youth) and his affairs, along with copies of any court order, agreement, or other instrument upon which your organization relies for such authority,” wrote Phillips.

If the agreement doesn’t exist, Weechi may have no legal authority over the youth, who is celebrating his 15th birthday on Oct. 29.

The pressing matter is getting the youth his urgent medical care to further investigate the complications of his rare condition: Sprengel’s deformity.

The list of treatments he needs includes an ultrasound to confirm he doesn’t have related kidney damage, a known issue associated with Sprengel’s.

The youth has never had an ultrasound, according to his medical records, from the time he was first diagnosed when he was three years and 11 months old right up to the present.

And not when the referral was made by a doctor last December. He has been waiting this entire time.

Customary care is generally unique to First Nations child welfare agencies, known as Indigenous Wellbeing Societies in Ontario, which means the child’s parent or First Nation agree to place the child in care of the designated agency.

When both the parent and nation agree it’s a voluntary agreement but consent can be revoked.

Back in July, lawyer Julia Tremain, also of Waddell Phillips, requested the agreement on behalf the youth’s caregiver who has been desperately pushing to get him the medical attention he needs for over two years. But the caregiver has no legal authority to make appointments herself.

It’s not unprecedented for there to be no agreement with Weechi. Just last week a judge returned a child to the biological mother after it was determined there was no customary care agreement in effect because it had expired in 2018, according to the judge’s decision.

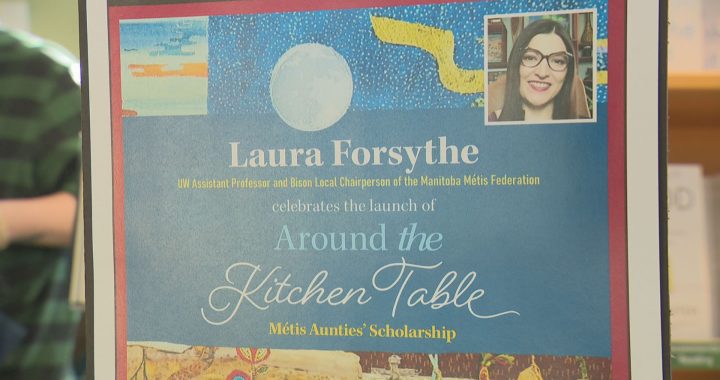

A recent APTN News story reported that medical records indicate the First Nation youth missed years of medical checkups, including a referral to a specialist to treat his Sprengel’s, a rare congenital disorder where one shoulder blade is larger than the other.

Related: First Nations youth in care likely deformed for life, blames child welfare agency

APTN is calling the youth Daniel — not his real name — to protect his identity.

“Every morning when I wake up and reach my left arm up in the air to get in the shirt, I get this really sharp pain and it lasts for about a minute. It’s like stubbing your toe, times two. It just doesn’t feel good,” Daniel said from his home in northwestern Ontario.

“I just get sudden strikes of pain in my back … [It] hurts more playing sports.”

Because his deformity wasn’t addressed at a young age, and he has been in care of Weechi since he was days old, doctors say he may be deformed for life.

His left shoulder blade is smaller than the right and it’s causing him pain every time he tries to use his left arm, which has a limited range of motion.

Sprengel’s can be corrected with surgery that is most effective when the child is around three and eight-years-old, according to several studies online, but Daniel never got surgery, despite records showing officials suspected the deformity just before he turned four in late October 2009.

Then there were gaps in his medical records for almost five years in total.

The medical records indicate Weechi has done little to address this in the last couple of years resulting in the youth missing key medical appointments needed to determine his next steps for potential surgery.

Most recently he has been waiting nearly a year to get a CT scan and the aforementioned ultrasound. Records show the referrals were made but Weechi never told the youth’s caregiver when the appointments were, because by law they had to be directed through Weechi. Attempts to have them rescheduled have been unsuccessful.

Because there has been no response to several requests for the agreement, Daniel and his caregiver do not believe one exists because he has no status card and was never registered with the First Nation for which Weechi oversees.

The same goes for his two older brothers, 16- and 18-years-old, who APTN recently interviewed.

They both confirmed they do not have status say they are not members of the band, despite all being in care since they were young.

Both also have scoliosis, however the eldest has a very minor case. The 16-year-old has a much more severe case that developed four years ago and is also still waiting for surgery.

“I am sure we will get the help we all need for our help as soon as possible,” wrote the 16-year-old in an Instagram chat with the brothers and APTN.

“One we may be weak, but together we are strong,” replied Daniel.

All three brothers had the same specialist, Dr. Peter Clark, an orthopedic surgeon in Thunder Bay. But Clark has admitted in the records he doesn’t have the qualifications required to treat Sprengel’s and referred to textbooks to diagnose.

Daniel knew he had older brothers, despite often going years without seeing them, but just found out two years ago he has four younger siblings still with the biological mother.

It’s not known whether others in the family have Sprengel’s but Clark points to it in the records.

“There is a family history of multiple congenital anomalies in the family and scoliosis,” Clark wrote Sept. 18, 2019.

While the children had the same specialist and medical records show Weechi was provided with all of Daniel’s records, Norma Spencer, the current supervisor of the First Nation’s child welfare team and long-time worker, expressed shock a couple years ago when the caregiver told her of Daniel’s condition.

This is revealed in a string of text messages, which were provided to APTN, between Spencer and the caregiver who first took Daniel in April 2018.

The first message is dated July 2, 2019.

“When I asked about (Daniel) I was told by Weechi that he had no congenital issues or anything in the past. He was assessed when he was 3/4 and saw a specialist. They diagnosed him as likely having (Sprengel’s) deformity but mild. It has become pronounced as he has become older, based on this most recent assessment. He is being sent back to the specialist.”

Spencer responded about something else, twice, and not about what the caregiver just wrote.

The caregiver responded: “Can you see the pic with his congenital issues?” (She had sent Spencer a photo of the child’s back).

“Wow he might have scoliosis also like (his older brother).”

“Actually, something more rare,” said the caregiver.

The caregiver wrote again on Sept. 19, 2019 that they have to do all sort of tests now and that Daniel has to go to The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) in Toronto.

Spencer responded: “Omg”

The caregiver explained the severity of the problem and that he may have organ damage because it was never tested as a child and is a known side effect of Sprengel’s deformity.

This is why Daniel needs to have an ultrasound.

The caregiver explained to Spencer that Sprengel’s will only get worse as he grows.

Spencer responded: “Ho crap i dont know what to say (sad face emoji) That’s friging sooo sad.”

Today, the caregiver is exhausted from trying to help Daniel but said she is going to continue to fight for him.

“Who is accountable to the child when improper file management causes harm to them?” she asked.

As it turns out, Phillips has a team of lawyers now looking into Weechi as more cases have come to light.

But Phillips doesn’t just have lawyers involved.

“Many people are reaching out with not just stories but actual evidence. People from the inside and former staff,” said Derrick Snowdy, an Algonquin private investigator.

“If this were anything but First Nations children it would be leading the news across the country.”

Spencer didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment, over the span of nine days, nor did the chief of the First Nation Weechi is purporting Daniel is tied to, despite no status or membership.

Laurie Rose, executive director of Weechi, also hasn’t responded.