By Rob Smith

APTN Investigates

More and more Indigenous people like James Louie may be coming forward accusing governments of genocide, but it’s a long road ahead if they want to prove it in a court of law.

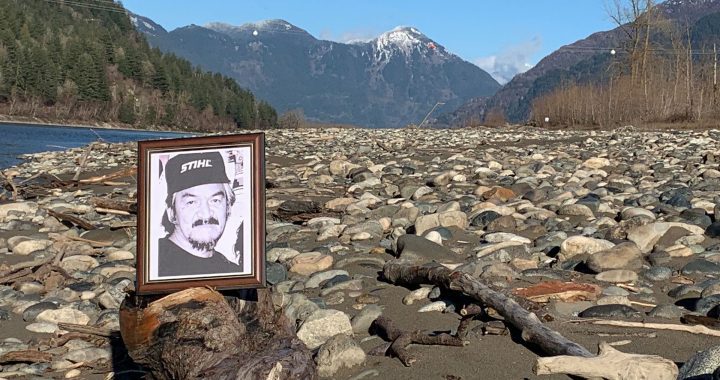

Louie journeyed to the United Nations in 2007 to testify before the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. At that time Canada had yet to adopt the UN Declaration on Indigenous Rights (UNDRIP).

His argument before the panel was the Lil’wat Nation are a sovereign people. Without a treaty, Canada’s actions of assimilation and its attempts to break down their culture were illegal. He asked the forum to use the Declaration to augment the UN’s convention on genocide. Specifically, Article 7 of UNDRIP which reads:

Indigenous peoples have the collective right to live in freedom, peace and security as distinct peoples and shall not be subjected to any act of genocide or any other act of violence, including forcibly removing children of the group to another group.

Louie will make the same argument before, another international body, the Organization of American States, on behalf of a Lil’wat woman who had her children taken by social services.

It’s important to note that Louie is doing is raising the specter of genocide before a human rights body, not a court of law.

Kathleen Mahoney, a law professor with experience in this area, says it’s a very interesting and important topic. But very complex.

“It’s one thing to say it happened. It’s quite another to do something about it,” she said.

Around the world Indigenous peoples are beginning to speak more and more in terms of genocide to describe what happened to them.

For Mahoney, the biggest challenge in a criminal action would be to prove intent. And there is a factor of timing. The U.N. Convention on Genocide was adopted in 1948.

“There is no retroactivity in the genocide convention allowed,” she said.

So any Indigenous group would have to find the basis of a claim in other forms of international law, something Mahoney said is complicated but not impossible.

Right now the United Nations has set up two courts to hear actual charges of genocide: the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the International Criminal Court (ICC).

The ICC is set up to prosecute individuals, not states. In 2008, after a bloody war in the Darfur region, ten charges of war crimes including three counts of genocide were laid against Sudan’s President Omar al-Bashir. The Sudanese government appealed, arguing the ICC has no jurisdiction in its country.

The ICC would not be a venue available for Indigenous people in Canada to find relief because any official in Canada that could possible face a charge is long dead.

The ICJ is designed to prosecute states that participate in or design genocidal activities. But another state — not an individual group — would have to step forward and make the charge.

Mahoney says that’s extremely unlikely. And really any judgment at the UN can’t be enforced within the borders of a nation that won’t recognize that judgment. It would be a moral victory and not much, she said.

To bring a case foreword in a domestic court would be difficult and even if it got to court, the outcome could be negative.

In 2013, a Guatemalan court found former leader General José Efraín Ríos Montt guilty of genocide. Ten days later the conviction was thrown out despite the overwhelming evidence of the murder of 1,771 Maya Ixil Indigenous people. Twenty-nine thousand of them were displaced along with numerous cases of sexual assault and torture during Rios Montt’s 17-month rule in 1982-83.

In 2000, Canada’s own Crimes Against Humanity War Crimes Act became law. It adopted international statutes as domestic law. But critics point out that only the attorney general of Canada can bring charges forward.

Essentially, Canada would have to charge itself with genocide.

Mahoney says Indigenous people of Canada could get the government to admit to genocide with political pressure. Internationally, Canada has set itself up as a champion of human rights; that reputation can take a hit if more of its dark history is revealed on the international stage, she said.