Sea lice attached to a juvenile salmon in Clayoquot Sound. Advocates say the stock will go extinct if Canada doesn't act soon. Photo courtesy Alexandra Morton, May 2018.

The federal government is abandoning the health of wild salmon in B.C., and ignoring Indigenous knowledge despite evidence the fish are being sickened by controversial open-net fish farms, advocates say.

On Friday during question period, NDP MP Gord Johns again attacked the Trudeau government for ignoring the pleas of people who say they’re trying to save the Pacific salmon stocks and who want fish farms shut down.

“The minister can’t promote open-net salmon farms and be a protector of Pacific wild salmon,” he put to the government. “Open-net pen farms increase the risk of disease and sea lice in wild salmon – by choosing to defend these farms the minister is ignoring local and Indigenous knowledge… When will the Liberals make good on their promise and remove the promotion of open-net fish farms from the Department of Fisheries mandate?”

One of the recommendations of the Cohen Commission, a $36-million study of the collapse of sockeye salmon stocks in B.C., was for the federal government to stop promoting “salmon farming as an industry and farmed salmon as a product.”

The government announced that it would be consulting with First Nations in the Discovery Islands area about fish farms ahead of a licensing review in December.

“Our government is committed to transitioning away from open-net fin fish aquaculture in British Columbia in a responsible way,” said Terry Beech, parliamentary secretary to the minister of Fisheries and Oceans. “Part of that responsibility is to consult meaningfully with affected First Nations and that is exactly what our government is doing.”

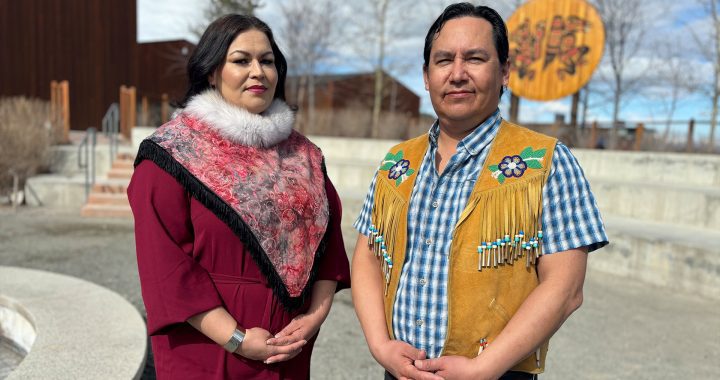

Bob Chamberlin, a First Nations leader in B.C. who is lobbying Canada to close the farms, agrees with the NDP.

“It’s a conflict-of-interest for DFO,” he said, “because promoting fish farm interests is in direct contradiction to its primary responsibility of protecting the health and abundance of Fraser River salmon.”

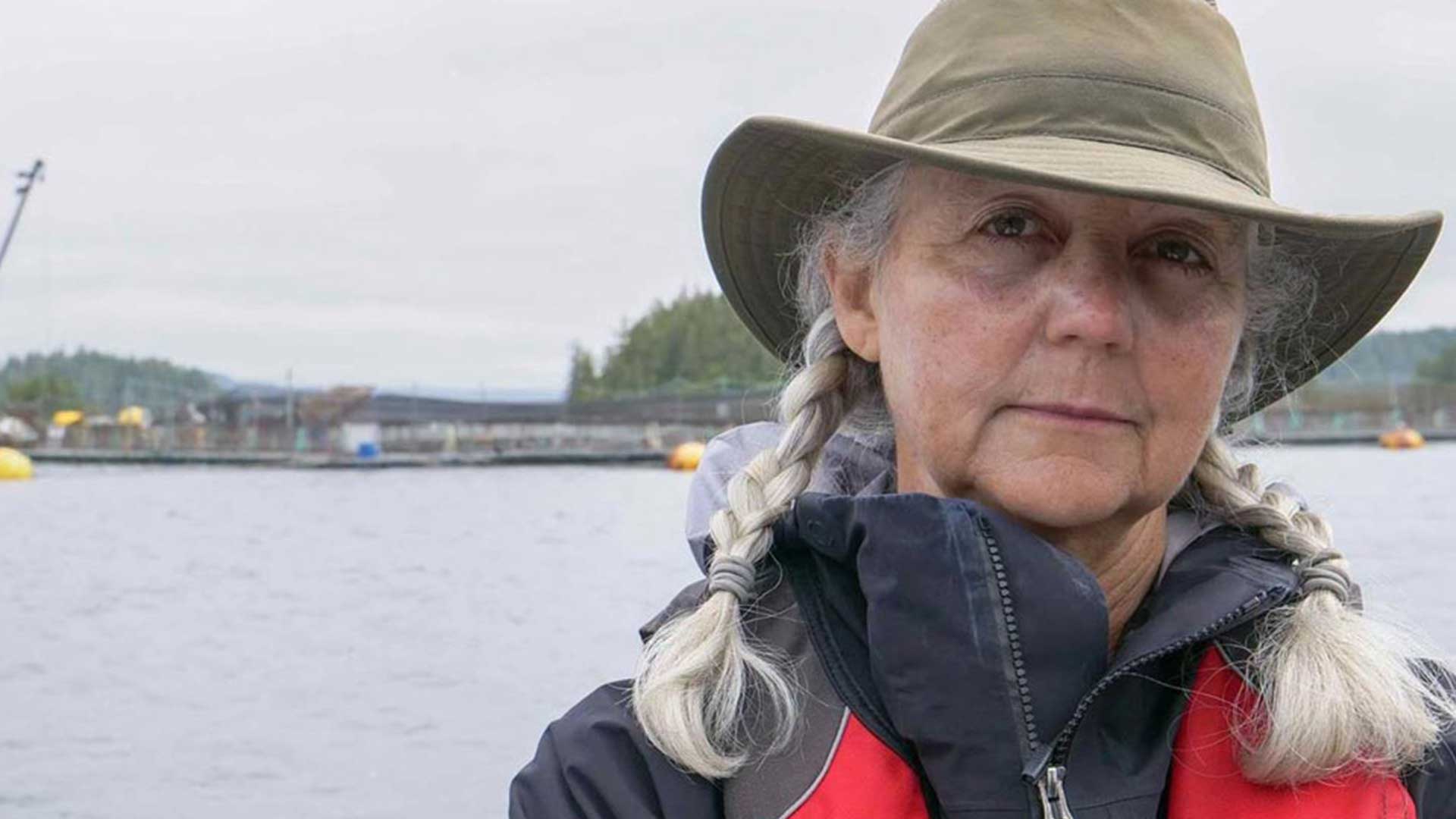

Alexandra Morton, a marine biologist who is now running for the B.C. Green Party, says she’s “disgusted” by the actions of Canada through the DFO.

On Monday, DFO announced the 18 farms around the Discovery Islands posed “minimal risk” to the wild salmon population, and promised to consult with seven First Nations nearby.

“There is something very foul afoot with this,” Morton told APTN News. “They are overseeing the extinction of a fish that feeds this entire eco system.”

Chamberlin said Monday’s announcement coupled with this season’s poor Fraser River wild salmon run, shows DFO has lost its way.

“They’ve abandoned wild salmon in B.C.,” said Chamberlin, who believes the farms are infecting young wild salmon with pathogens and sea lice along the spawning route.

The Cohen Commission of Inquiry into the Decline of Sockeye Salmon in the Fraser River was struck by the Harper government in 2009. It cost $26 million and made 75 recommendations, 11 of which related to reducing the impact of farmed salmon on Fraser sockeye whose numbers are in steady decline.

Recommendation No. 19 said the controversial farms should be closed by December 2020 if they pose more than “a minimal risk” to the annual wild salmon migration.

But on Monday, DFO said the farms don’t pose a threat despite growing opposition from First Nations communities, commercial and sport fishing groups, eco-tourism operators, scientists and more.

Last week, Chamberlin said a consortium of 101 B.C. First Nations — including five of the seven DFO said it would now consult with — demanded the farms be removed.

Those seven First Nations are Tla’amin, Klahoose, Homalco, K’ómoks, We Wai Kai (Cape Mudge), Wei Wai Kum (Campbell River) and Kwiakah.

Chamberlin likened the news of consultation to the way Prime Minister Justin Trudeau promised to hear from all sides before expanding the Trans-Canada pipeline.

“He said, ‘The pipeline will be built.’ And then he said, ‘We’re going to consult with Indigenous peoples.’ Consultation is an entirely Crown-controlled process.”

Read More: Pacific Salmon Stocks

Morton said the numbers help tell the story: Fewer than 300,000 wild salmon are expected to spawn this year from the millions that used to return on an annual basis.

“The Elders used to say they could probably walk across the Fraser (River) along the backs of salmon,” said Art Adolph, former chief of the Xaxli’p First Nation near Lillooet.

“I’ve noticed the difference from my childhood until now. There used to be a lot.”

But now, interior and coastal bands believe some species of salmon are in crisis.

“There needs to be more management by the federal and provincial governments in regards to all the impacts to wild salmon,” said Adolph, rhyming off factors like logging, mining and development in addition to the risks posed by fish farms.

“They’ve bent over backwards to try and ensure that companies and corporations are able to access land and resources that we depend on in order for our culture to survive.”

Morton concurred.

“DFO is aligning itself with three Norwegian companies (that run these farms) as some kind of wonderful path for economic prosperity and jobs,” she said.

“But it’s not taking into account the health of wild salmon.”

Morton said what DFO did and didn’t review speaks volumes.

Fisheries Minister Bernadette Jordan said Monday DFO conducted nine peer-reviewed risk assessments into nine separate farm pathogens.

But her department did not test the impact of sea lice or say why.

Morton said while sea lice occurs naturally, she has seen heavier loads than now and they are killing young wild salmon, which she blames on the farms.

Chamberlin listed numerous reviews, studies and investigations he said were scientific proof the farmed fish were infecting wild fish.

“These are not activist views,” he said of pathogens like piscine reovirus (PRV) found on wild salmon.

“These are scientific views.”

Chamberlin noted Canada had a legal duty to consult Indigenous peoples. But it should also act on what it hears, he said.

“B.C. salmon – for First Nations – it’s not just a menu choice. It’s who we are.”

Morton said she was running for a provincial seat to try and make change from inside the system and work with First Nations.

“I wish I could vote for them,” she said of the way Indigenous governments are standing up for salmon.

However, science also speaks for the fish, said Kristi Miller-Saunders, the head of molecular genetics for DFO in Nanaimo, B.C., who was once muzzled by Harper’s administration.

“It’s a fluid situation,” she said in an interview with APTN. “They (DFO) made the decision (and Monday’s announcement based) on information they have at the time.”

Some of that information came from her most recent study, which contains a decade of data and should be released in about six months.

Miller-Saunders, who testified at the Cohen Commission, wouldn’t reveal what her data shows but said it will recommend one side pump the brakes. Only she wouldn’t say which side.

“I don’t have an opinion on fish farms,” she added. “I keep following the science.”

DFO’s data applies only to Fraser River sockeye, she added, not coho or chinook.