Jorge Barrera

APTN National News

Amos Blackhawk’s record ends when he was 14 years-old with one word typed into the last column next to his name on the St. Mary’s Indian Residential School’s quarterly report for June 30, 1943: dead.

Three years earlier, on Jan. 9, 1940, Blackhawk was 11 and sick with tuberculosis. He and three other ailing children were waiting for a taxi arranged by A. G. Hamilton, the Inspector of Indian Agencies in Manitoba, to take them from the Catholic-run St. Boniface Sanatorium in St. Vital, Man., to one run by Ottawa in Selkirk, Man.

The taxi would never arrive after a senior nun intervened to stop the transfer while the Archbishop sorted out the situation with the Minister of Mines and Resources who was responsible for Indian Affairs and the running of residential schools. It was a series of interventions by Catholic officials, including the principal of St. Mary’s residential school in Kenora, Ont., and the Archbishop of St. Boniface, that led the boy to wait for a taxi.

The federal government was refusing to pay for the four students’ stay at St. Boniface and wanted to transfer them to the Dynevor Indian Hospital in Selkirk.

Blackhawk had become a pawn in a power struggle between the Church and Ottawa over students who contracted TB in Catholic-run residential schools. While the Catholic Church was counting souls, Ottawa was counting coins because the Second World War was placing a heavy demand on the treasury.

This battle, waged through letters and telegrams between Catholic and federal officials and the manipulation of the sick residential school students’ parents, is a little known part of the Indian residential school story.

Tuesday’s planned release of a final report by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), which is expected to say at least 6,000 children died in the schools, and the establishment of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation in Winnipeg which will hold a multitude of historical residential school records, will provide the largest gateways yet into this dark period and its unexplored corners.

Part of Blackhawk’s story and that of the Catholic Church’s underhanded tactics and intense lobbying to force Ottawa to send TB-infected students at Catholic residential schools to Catholic sanatoriums are contained in documents unearthed as part of another thread that won’t end with the TRC’s report.

The documents, obtained by APTN National News, form part of the basis for a legal battle launched by some residential school survivors to classify the Fort William Sanatorium, which sat in Thunder Bay, as a residential school under the multi-billion dollar settlement agreement that created the TRC.

Residential school survivors can only receive compensation for years spent at residential schools listed in the settlement agreement and the Fort William Sanatorium did not make the cut.

Read more on the issue here: Federal cabinet confidence prevents release of documents on attempted inclusion of sanatorium as residential school: document

And here: InFocus: Sanatoriums, Indian hospitals

Justice Paul Perell, of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice, is expected to hold the first hearing on the Fort William Sanatorium case on Oct. 15.

The boy from Northwest Angle 37

Blackhawk was diagnosed with TB sometime in October 1939. The boy from Northwest Angle 37 was attending St. Mary’s residential school in Kenora, Ont. His name is consistently misspelled in correspondence as “Emos.”

Shortly after he was diagnosed the principal of St. Mary’s, Father J. Lemire, informed Saint Boniface Archbishop Emile Yelle of the diagnosis. Yelle directed him to send the ailing student to the St. Boniface sanatorium in St. Vital. Blackhawk was admitted there on Oct. 30.

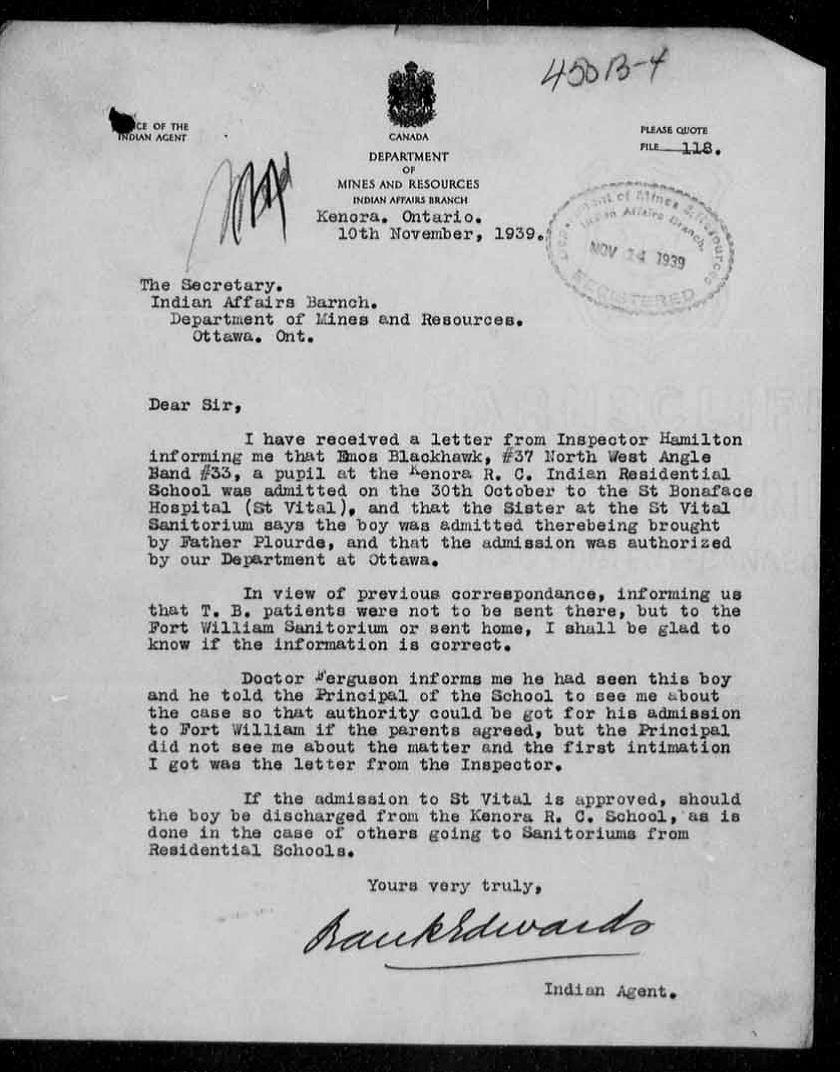

Indian Affairs branch officials caught wind of the move a little over a week later. Indian Agent Frank Edwards hammered out a letter to a senior branch official wondering what to do since TB-infected students from that school were supposed to be sent to the Fort William Sanatorium.

“In view of the previous correspondence, informing us that T.B. patients were not to be sent there, but to the Fort William sanatorium or sent home, I shall be glad to know if the information is correct,” wrote Edwards, in a Nov. 10 letter.

Seven days later, a letter was sent to the St. Boniface Sanatorium that the federal government would not be picking up the tab.

“The department will not be responsible for the maintenance of the patient,” said the department’s missive.

For the next two months, the matter bounced up the bureaucratic chain to the deputy minister’s office and back down again. Letters were sent from the sanatorium to the department and back again. The department insisted it would not pay for the treatment because Blackhawk, and the three other students, were transferred without any federal authorization.

Finally, the department decided to move Blackhawk to the Dynevor Sanatorium in Selkirk which found the 11 year-old waiting for the taxi that never arrived on Jan. 9, 1940, as a result of the intervention by the senior nun.

By this time, Blackhawk’s X-rays showed a “slight increase in the disease” and that “he should definitely be kept under treatment,” according to a report from a doctor that same month.

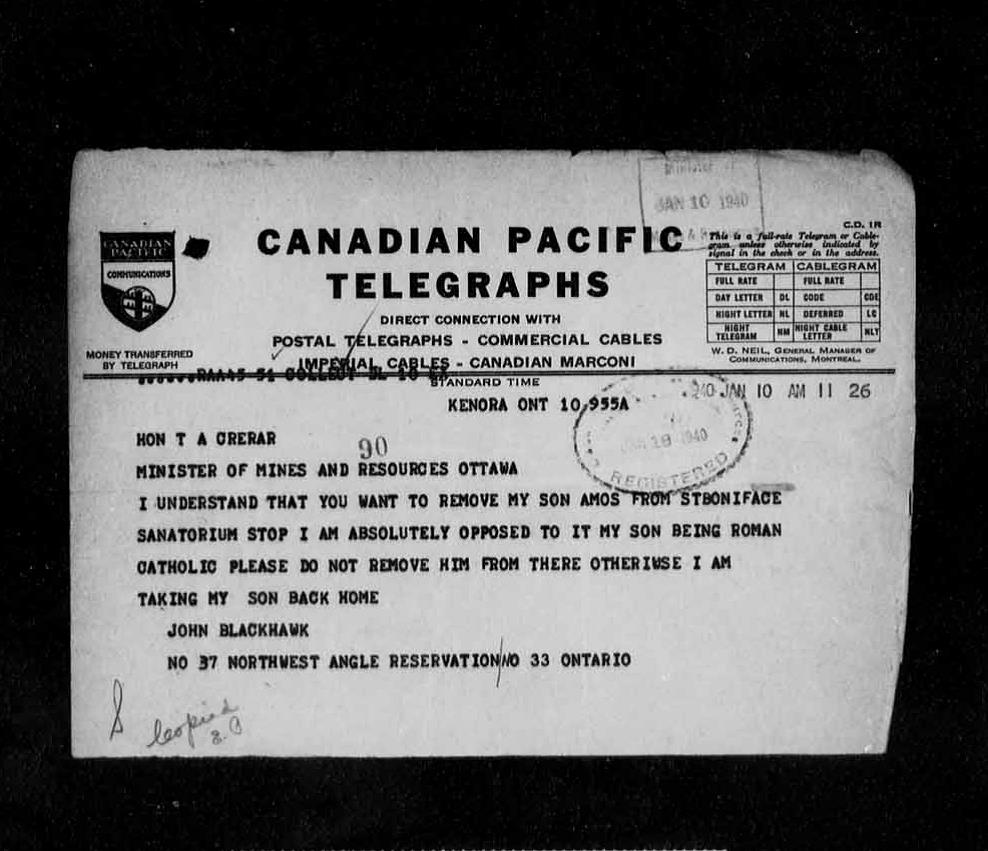

The next day, Minister of Mines and Resources T. A. Crerar received a telegram, sent over Canadian Pacific Telegraphs, from Blackhawk’s father John Blackhawk.

“I understand that you want to remove my son Amos from St. Boniface Sanatorium,” it said. “I am absolutely opposed to it, my son being Roman Catholic. Please do not remove him from there otherwise I am taking my son back home.”

Crerar received a second telegram the next day.

“Please advise me by wire care St. Mary’s Indian School what you propose to do with my son Amos Blackhawk so that may take necessary action,” it said.

The department did have a policy giving parents a say over what happened to their sick children attending residential schools and the telegrams suddenly complicated the situation.

Officials were, however, suspicious as to whether Blackhawk actually sent the messages and tasked Indian Agent Edwards to investigate.

“If John Blackhawk should, by any chance, not be at Kenora, or not have been there when the telegrams were sent, please inform the department by telegram without waiting to find him,” said a letter to Edwards from a senior Indian Affairs official, dated Jan. 12, 1940.

John Blackhawk sent a letter to Edwards also dated Jan. 12. He said he wanted his son to stay at St. Boniface.

“I quite understand I am free to have my son in any hospital I would like, subject to the approval of the department,” Blackhawk’s type-written letter said. “The principal of the St. Mary’s Indian School…advised me to leave the boy where he is now.”

Edwards found Blackhawk the same day. He said Blackhawk gave him a different version of the story.

“John says he does not know anything about the hospitals and he really does not mind what hospital his son is at,” said Edwards, in a Jan. 13 letter written to the Secretary of Indian Affairs. “If the principal had not influenced the Indian, I do not think he would have minded what hospital Amos was in, but he says if the boy is not cured in a few months he wishes him sent back to the reserve.”

Edwards said it was Father Lemire, the principal of St. Mary’s, who wrote and sent the telegram on Blackhawk’s behalf.

“The Indian not paying anything for the wire,” said Edwards.

Ottawa worse than ‘Adolf Hitler’

The Blackhawk affair was not a simple misunderstanding. It was another skirmish in a paper war involving the lives of ailing students that stretched back to at least 1935 and emanated from the very top of the Catholic hierarchy in Canada.

That year, Cardinal and Archbishop of Quebec Jean-Marie-Rodrigue Villeneuve requested a letter be sent to Dr. Harold W. McGill, the deputy superintendent general, Department of Indian Affairs, requesting the Indian Affairs’ education branch, which ran residential schools, be split into two sections, one Catholic, one non-Catholic.

“The problem of hospitalization among the Indians, either from the point of view of general hospitals or from the point of view of sanatoriums for the cure of tuberculosis, stirs up much anxiety among those who are engaged in the evangelization of the Indians,” stated the letter.

The letter, dated March 21, 1935, went on to accuse the Indian Affairs branch of an anti-Catholic and anti-French bias. The letter then breaks down the statistics of Catholics in Indian Affairs offices in Ottawa and finds only 13 out of 58 seek out confession. Of this number, four are stenographers “and another is a messenger.”

The letter concluded the state of affairs “would be still worse” if the numbers included officials outside Ottawa.

“How can one overlook in the foregoing an evident determination to alienate from the administration of Indian Affairs everything that is Catholic and still more perhaps, everything that is French,” said the letter. “Is it not high time that a protestation be entered against this present condition of things in order to obtain its redress?”

McGill responded on April 1, 1935, saying the department takes no position on religious affiliation when choosing to send “sick Indians” to sanatoriums.

“Where custom has produced a situation which might indicate otherwise, the advantage would seem to have been on the side of your Church,” wrote McGill.

On Sept. 1 of that same year a six year-old boy named Amos Blackhawk was sent to the St. Mary’s residential school. By the time Blackhawk turned 10, the Church was still lobbying strenuously to keep control of students that fell to tuberculosis in its schools even as infection-related deaths were continuing to rise.

On April 12, 1939, the federal Department of Health’s director of tuberculosis prevention sent a letter to McGill expressing concern about TB rates in Ontario. In 1938, 114 “Indians” died from the infection and on Manitoulin Island there were 13 deaths the previous year.

“I am particularly anxious about the Manitoulin Indians,” said the letter.

The Department of Health concluded it was against transferring cases between provinces. The department said it would be best if all “Western Ontario” cases be handled by the Fort William Sanatorium.

The Catholic Church, however, was still battling to send TB infected children from its Western Ontario residential schools at McIntosh, Kenora and Fort Frances to the St. Boniface Sanatorium in St. Vital.

Rev. J.O. Plourde, the general superintendent for the Oblate Catholic Indian Missions, sent a stinging letter to McGill, comparing the department’s attitude to Adolf Hitler.

“Even Adolf Hitler has not gone as far as that in his treatment of Catholic children,” said Plourde, in a May 11, 1939, letter.

For the department, however, the matter came down to dollars and cents in a time of war.

According to numbers included in correspondence from federal officials, it cost about $2.30 a day to care of a patient at St. Boniface, while for the government-run sanatorium in Selkirk the cost was closer to $1.30 a day.

Manitoba’s TB cases were also getting expensive.

Over a nine-month period in 1940, Ottawa spent $38, 700 treating TB among 9,000 “accessible Indians” in Manitoba. This was compared to the $14,642 spent over the same time period in Quebec treating cases among 8,000 “accessible Indians.” The department only had $300,000 set aside for tuberculosis control among 60,000 “accessible Indians” across the country that year. Manitoba was about to break its budget of $45,000, according to one memo.

There was also the war.

“When our estimates were being considered by Treasury Board this spring, I was very much afraid that we would have to curtail our tuberculosis programme in view of the financial requirements for war purposes,” wrote Minister of Mines and Resources T. A. Crerar to Winnipeg Archbishop A.A. Sinnott, in a letter dated June 15, 1940. “The situation in Europe appears to be steadily growing more serious. The fate of civilization and perhaps the future of Christianity for centuries to come, hangs in the balance.”

The Blackhawk family

It remains unclear how long Amos Blackhawk remained at St. Boniface in 1940. The paper trail runs cold. According to the St. Mary’s quarterly reports, Blackhawk was listed “at home” between Jan. 1, 1941 and Sept. 30, 1941.

By Jan. 12, 1942, Blackhawk’s TB infection grew worse. Edwards reported that the infection was so bad the boy became a “menace” and he was sent to St. Joseph’s Hospital in Kenora. From there he was transferred to the Dynevor Sanatorium in Selkirk where he appears to have remained until his death.

Amos appears to have been the second of six Blackhawk children who all attended St. Mary’s. His oldest brother Clarence entered residential school at age eight in 1934. His younger brother Chris entered residential school at age seven. The next boy Joseph entered at age seven in 1939. Their sister Mary entered the school at age eight in 1941. The youngest Louise, entered at age seven in 1942.

Joseph, Mary and Louise Blackhawk all appear to have contracted TB at one point.

Father Lemire also tried to stop Joseph Blackhawk’s transfer to Dynevor in November 1941. Department officials accused the principal of putting the boy’s health and those of the other students in the school at risk.

Joseph Blackhawk was listed as “dead” in St. Mary’s quarterly report for Jan. 1 to March 31, 1946.

The children’s mother also contracted tuberculosis. The Indian agent saw her got on a train to the Fort William Sanatorium on Feb. 11, 1943. She never arrived at her destination. In a letter, the Indian agent recommended police be notified.

@JorgeBarrera

Poor innocent children taken from their families and treated in such a despicable manner. It’s like my son said recently, there are evil people to be scared of.

Very sad, im so sad, for my dad for my uncles my family!!….our famlies!!…. I cant speak my own tounge because its still hard to teach us!!.. Even worse its hard for us to learn!!!.. My dad to this very day is forced to rememebr painful things that happened to him and my uncles and aunties…..just to prove to agencies he was truley apart of these actions!!….. They claim to wanna help him, so far i see my Dad having to tell these stories!!!…..