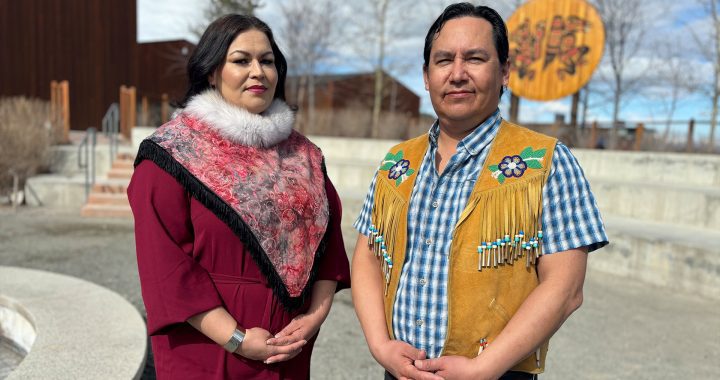

Autumn Windego seen here at Rainy River First Nation last September. Kenneth Jackson/APTN photo

Autumn Windego knows this story could lead to her being exiled from Rainy River First Nation (RRFN) in northwestern Ontario.

But the 25-year-old Anishinaabe mother of two wants the world to know she believes the RRFN band council is trying to bully her into being quiet on the current crisis in child welfare.

It begins with a letter she received Jan. 4, 2021 from the band office saying it wont’ tolerate her “continued attacks” against the RRFN’s child protection team.

Band manager Sonny McGinnis told Windego he was directed by council to put her on notice.

“Your continued attacks against our Rainy River First Nation Community Care Program will no longer be tolerated and result in the issuance of a Band Council Resolution authorizing your immediate removal from our properties and lands of Rainy River First Nation,” said McGinnis.

“I trust you will heed this warning with the utmost seriousness and modify your behaviour and conduct accordingly.”

But what are the attacks?

RRFN doesn’t specify in the letter, nor does it in response to inquires from Windego’s lawyer seeking clarification.

“As far as Chief and Council is concerned the letter written to Autumn Windigo is self explanatory and requires no explanation to you as her counsel,” wrote McGinnis, in a Feb. 10 email to Windego’s lawyer, Douglas Judson.

“The letter written to Autumn Windego dated January 4, 2021 remains in effect.”

There’s been no further communication from the band office.

Windego believes the “attacks” are for being a source in an exhaustive APTN News investigation late last year that dug into RRFN and Weechi-it-te-wn Family Services, as well as other communities.

RRFN is one of 10 First Nations under Weechi, a child welfare agency licensed by the Ontario government and based in Fort Frances, Ont.

Windego was a source in two stories, including an APTN Investigates documentary, The Death Report Part 2, that aired Dec. 11.

She spoke of her time growing up in care and then working for the RRFN child protection team before quitting last summer.

Here is what she said in that story:

“You can put a complaint in with chief and council and chief and council doesn’t do anything. And then you can make a complaint to Weechi-it-te-win and [Executive Director] Laurie Rose doesn’t do anything, which sucks because then when a kid who is already going through so much, sometimes they might take their own life, or sometimes they might run away … or not even being seen, their services aren’t being met. Which is ultimately leading up to kids, I feel like, just set up for failure,” Windego said.

Today, she is letting her lawyer speak for her.

“To see this reaction it seems very heavy-handed and it seems like an attempt to keep her from speaking about what are really matters of community and public interest,” said Judson, on Nation to Nation with host Todd Lamirande.

Windego lives in a band-owned home with her partner Tyler Medicine, and their two young children. Medicine is a member of the band, but Windego is a member of Siene River First Nation, also in northwestern Ontario.

So does RRFN have the authority to sign a band council resolution and banish, or BCR her?

According to Winnipeg lawyer Michael Paluk, the band council does not.

Paluk had a case before the Federal Court about 20 years ago involving two clients who were “BCR’d” from their First Nation which the court later overturned.

He said the Federal Court ruled that a band council resolution is simply a record of a decision made at a band council meeting.

“It’s not any kind of enforceable instrument, like an order or a bylaw,” said Paluk.

“I still hear from people that say ‘I’ve been BCR’d’ like it’s somehow become a verb.”

He said the Federal Court said the First Nation needed to have a clearly established bylaw if it wanted to banish people, but there doesn’t appear to be any such residency bylaws at RRFN.

N2N wasn’t able to find any on its website, members of the community were unaware of one existing and the band council never responded to N2N when we asked.

In fact, the band council didn’t respond to any of our questions, including how their attitude towards Windego changed so abruptly in less than a year.

It was just last July when an internal investigation confirmed harassment and conflict of interest complaints against Coun. Leona McGinnis in part based on the evidence provided by Windego.

“We found Autumn Windego to be a credible interviewee. We found that were was credibility to her words and actions and the way she presented herself,” said the investigation panel in its final report obtained by APTN.

“We have no doubt that she participated in this process in good faith.”

Where versions of events differed between Windego and Leona McGinnis the panel relied on Windego’s account.

Windego is the first in four generations of her family to raise her own children, after growing up in care herself as a Crown ward in northwestern Ontario.

“I was in lots of foster homes, some of them were good and some were really bad,” Windego said, in the Nov. 12 story. “I know I can help them, because I have been there.”

Now she waits to see if this story is considered an attack that will lead to her being forcibly removed from the home.

Watch her lawyer’s full interview on N2N below.