In recent months, human trafficking has made headlines in Canada as governments announce new legislation and new money to fight it.

But sexual exploitation is not a new problem.

“It’s been going on since the whole history of Nova Scotia,” says a peer outreach worker with the YWCA in Halifax. “People just don’t want to look at it.”

We’re not revealing this outreach worker’s identity so we don’t jeopardize her work with people at-risk, victims, and survivors of sexual exploitation.

“I go around the neighborhood as much as I can, doing work to talk about the real fear of getting trafficked, how easy it is to happen, the different ways that it can happen,” she says.

She knows firsthand. It happened to her at age 13.

“I heard once, if you can’t find the person, be the person,” she says. “When I was 13, I couldn’t find that person. So for me, I want to be that person. So that other kids don’t have to experience some of the horrors and traumas that I have.”

As a Cree, Mi’kmaw and African Nova Scotian, she brings her culture and life experience to her role with the YWCA’s NSTAY program – Nova Scotia Transition and Advocacy for Youth.

Her clients range from as young as nine, to age 12, up to women in their 40s.

“People, when they hear about sex trafficking, child sex trafficking, they think Philippines, they think all these other exotic places or different countries, when that industry is so big here in Canada,” she tells APTN Investigates.

“But they don’t see it. You don’t want to know that this is going on right here, because then you’ve got to wonder if your father or your brother or your uncle is the client.”

She says sex traffickers can be a peer, another woman, a person in a position of power, a pimp.

“And then there’s the boyfriend,” she says. “Everybody wants to be loved. We don’t dream any differently than anybody else. So, he becomes that Prince Charming, for whatever reason, in this sea of craziness.”

The Hollywood version of sex trafficking can happen. The victim is drugged, abducted, and forced into sex work. It’s called guerilla pimping.

But the trafficker’s biggest weapon is manipulation.

“They look for people with vulnerabilities or weaknesses and they exploit those. It’s part of what they call the grooming and recruiting process,” says RCMP Cpl. David Lane, who heads the inter-agency Nova Scotia Human Trafficking Unit.

He says it’s important people recognize the red flags.

“Some of the indicators would be that their daughter met Prince Charming, a new boyfriend that she’s totally in love with, who treats her better than anyone before.”

Lane gets calls from concerned parents and describes a common scenario; a new boyfriend, bearing gifts, a new look, a change in behavior. Their daughter becomes difficult to reach, and moves away.

“None of that would seem that it’s a crime but it’s a lot of the steps of the grooming process.”

Lane says trafficking is a hidden epidemic but one happening in plain sight.

“These traffickers are traveling with their victims in public, especially pre-Covid, in the airports, train stations, the bus stations. They’re getting stopped by police,” says Lane. “So it’s really a crime that’s happening in the open, I guess is the biggest surprise to most people.”

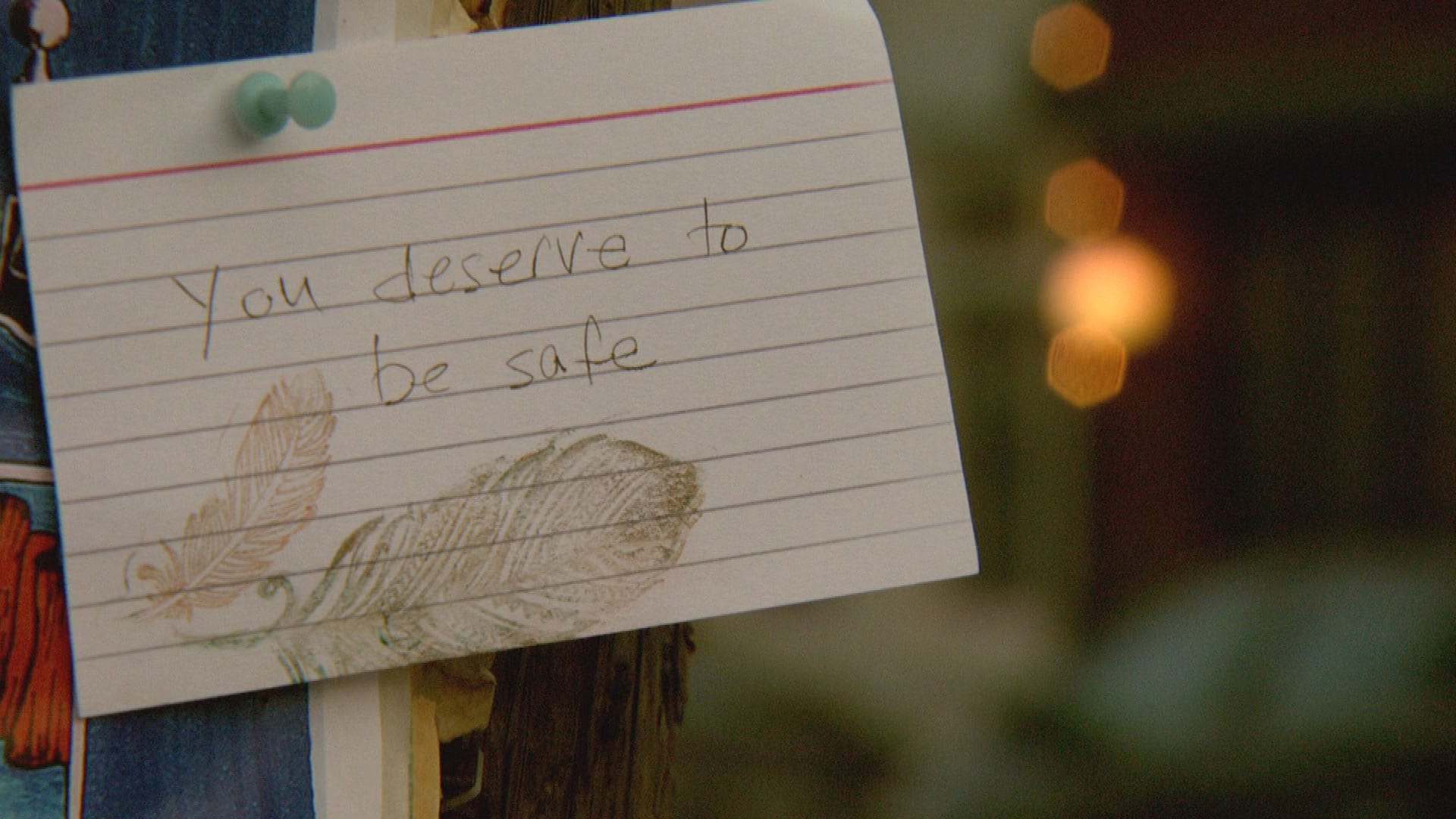

Sex trafficking is different than sex work. It’s exploitative and takes away the victim’s choice through manipulation, force, coercion, and threats.

It’s a complex crime to investigate. Victims may be fearful for their safety. Or they may think the trafficker is their boyfriend.

And trafficking doesn’t respect borders.

“I would say that’s one of our top issues, the multi-jurisdictional aspect of human trafficking,” says Lane. “Someone’s in Halifax today. We start a file and then they’re in New Brunswick or Quebec the next day.”

A recent report from the Canadian Centre to End Human Trafficking focused on highway corridors, including the TransCanada highway, and the 401 in Ontario.

The report concludes, “What is clear is that a key mechanism of exploitation employed by sex traffickers is leveraging the isolation of the victim, and their unfamiliarity with their environment, in order to profit.”

Human trafficking is big business. Globally, it’s a $150 billion dollar-a-year industry.

In North America, two-thirds of human trafficking involves sexual exploitation. In Canada, 97 per cent of victims are women and girls.

Since 2016, the provincial Human Trafficking Unit has engaged in a campaign to raise awareness.

“It’s not something that we can arrest our way out of,” says Lane. “The best human trafficking case is the one that doesn’t happen.”

For the Nova Scotia Native Women’s Association (NSNWA), prevention and education are key.

“A lot of people don’t understand that whole concept of human trafficking. Our own communities don’t understand it,” says Karen Bernard, director of the Jane Paul Centre in Sydney, Cape Breton.

The centre serves Mi’kmaw women-at-risk and is run by the NSNWA.

In February, 2021, the Mi’kmaw association received $386,000 in federal funding to develop a three-year project; the Nova Scotia Indigenous Human Trafficking Prevention strategy.

“What it’s going to do is increase the awareness of human trafficking and improve the quality of our indigenous people within this province specifically,” says Bernard.

In 2018, Nova Scotia made headlines for its high rates of trafficking relative to the rest of Canada.

Bernard says trafficking is hardly a new issue. For Indigenous women, it’s tangled with the history of colonialism.

“The young girl, Pocahontas, if that was her real name, was taken away. Again, you know, glorified in Disney movies,” says Bernard. “Nobody realizes she was, I believe, 12 at the time. This child was put into a child marriage. She was kidnaped. She was exported. She was taken away from our country.

“And this is where my whole piece comes from, regards to grooming our people right across the country, grooming our people for human trafficking, and this is where it began.”

Bernard says that pattern continued with residential schools and the Sixties Scoop.

“Our children are exported from their homes. They are taken in exchange,” she says. “All those factors that created this whole allowance to let our people believe that we are worth less than what we are.”

Bernard says that cycle continues today with Indigenous over-representation in the child welfare and the criminal justice systems, both of which make people vulnerable to trafficking.

Last year, the Nova Scotia government invested $1.4 Million dollars for prevention and awareness of human trafficking.

In 2019, the federal government launched National Strategy to Combat Human Trafficking, committing $57 million over 5 years.

If you need help or know someone who does, call the national toll-free hotline 1-833-900-1010 or go online at www.canadianhumantraffickinghotline.ca.