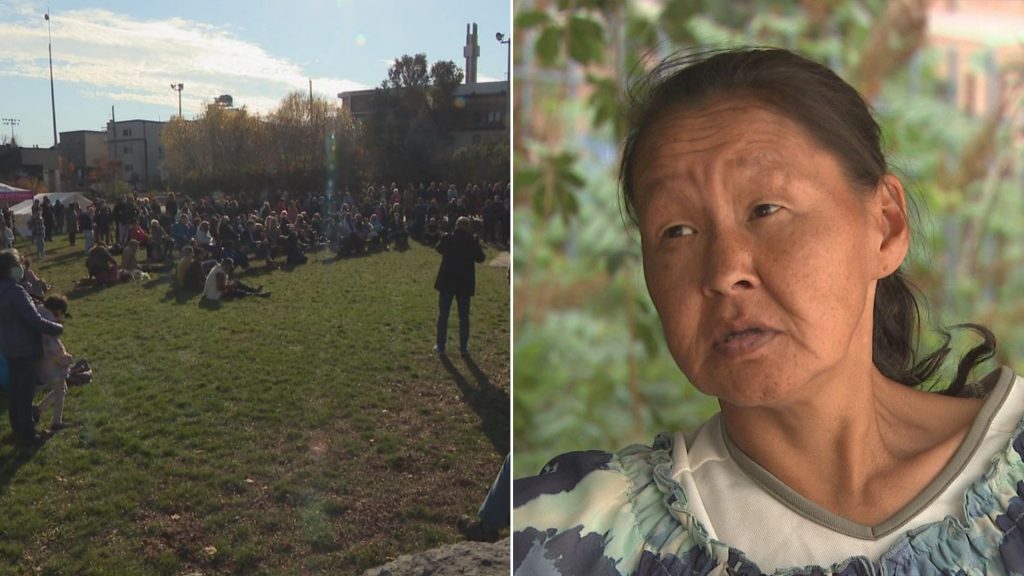

Annie Pootoogook and the park the is named after her in Ottawa.

Every day on his way to work in 2016, Veldon Coburn drove past Bordeleau Park, by the edge of the Rideau River near downtown Ottawa.

On a September day that year, while he drove past the park, Coburn heard on the radio that a body had been found in the river.

Days later, he learned that the person found in the river was Annie Pootoogook, a renowned Inuk artist who won the prestigious Sobey Art Award in 2006 and whose work has been shown around the world.

She was also the biological mother of Coburn’s adopted daughter, Napachie, who was four years old at the time.

Despite her success, Pootoogook struggled with homelessness while in Ottawa. Police investigated her death as suspicious, but no charges were ever laid.

This year, Sept. 19 marked the sixth anniversary of Pootoogook’s death. Napachie turned 10 years old the same month. Coburn said that at each anniversary, he wonders if he should be doing more to find answers for his daughter about what happened to her biological mother.

“There are so many questions left unanswered. What if Napachie starts asking in 10 years, ‘Why didn’t you ask more questions?”’ he said.

This anniversary was especially heavy, he said because it came just days after a 22-year-old Inuk woman was found dead in Ottawa.

Police say Savanna Pikuyak moved to the city in early September and responded to an ad on Facebook to rent a room in a three-bedroom townhouse near Algonquin College, where she had just started studying. She was killed Sept. 14.

Her roommate, Nikolas Ibey, 33, has been charged with first-degree murder.

Later in September, the remains of Mary Papatsie were found at a construction site in the city’s Vanier neighbourhood. Her family had declared the 39-year-old missing in 2017.

In a statement, her niece Tracy Sarazin said the family is now looking for “answers and justice,” and they are demanding a thorough investigation into what happened to Papatsie.

All three women moved to Ottawa from the North in search of better opportunities.

The Ottawa-Gatineau region has the third-largest Inuit population among major Canadian cities. According to the 2021 census data, the population increased by 35 per cent over five years to 1,730.

Coburn is a professor at the University of Ottawa, where he teaches and researches Indigenous politics. He said that the Inuit are farther behind in socio-economic development than First Nations or Metis.

“There has been deliberate colonial economic under-developments or -investments in them as people,” said Coburn.

Natan Obed, president of the national representational group Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, said it’s unacceptable that Inuit and Indigenous women and girls are still facing disproportionate rates of violence.

“There’s the sobering reality, the systems that are in place have a disproportionate risk for women and girls, just by their very nature,” said Obed.

Inuit communities in Nunavut are secluded, something Obed said not many people in the southern part of the country understand.

The difference goes beyond “living in a small town,” he said. In remote communities, the cost of living is high and housing is difficult to find. Access to services and opportunities, including health care and education, is limited.

That lack of resources has pushed many Inuit women like Pikuyak and Papatsie to leave.

But the road to better opportunities is also a pathway to potential violence. Obed said many people who are targeted find themselves in scenarios where they don’t have the resources to be able to return home and lack social support in southern cities. Some face homelessness or addiction, and isolation from loved ones.

The Native Women’s Association of Canada is working on upgrading a program called “Safe Passage,” which it has used to track cases of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls and to warn others about areas to avoid.

Judy Whiteduck, the group’s vice president of policy, advocacy and engagement, has been spearheading the project. She said putting the 231 recommendations made by the 2019 National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls into action must be a priority.

She said the challenges Indigenous people face are “forcing them to live in unsafe places.”

“Concrete supports are needed,” she said. “We will start to see the kinds of changes that need to happen.”

One of the inquiry’s recommendations is providing initiatives and programming to address the root causes of violence against Indigenous women and girls. Others include addressing disproportionate poverty rates and improving access to safe housing.

Obed said his organization is working to secure funding for five shelters. He said he is also in regular communication with RCMP Commissioner Brenda Lucki to ensure that it gets adequate data from police.

“We need to do more to ensure their safety, provide medical care closer to home, if not in home communities,” Obed said. He added that the rest of Canada needs to become aware of the dire need for better infrastructure in the North.

For the first few years after Pootoogook’s death, Coburn continued to ask Ottawa police for updates, but he said it has been years since he’s heard anything.

“One of these days, somebody’s got to reopen the case or just take a new look,” he said.

Coburn and his daughter have maintained strong relationships with her biological family in Kinngait, Nunavut. He said she will always be a Pootoogook, and he worries about the toll her biological mother’s death might have on her as she grows up.

“There’ll be a lifetime of, perhaps, psychic agony for Napachie of not knowing, because it feels like the cops have not done much.”