RCMP officers have enforced an injunction for Coastal GasLink for three years straight beginning in 2019. Photo: APTN file

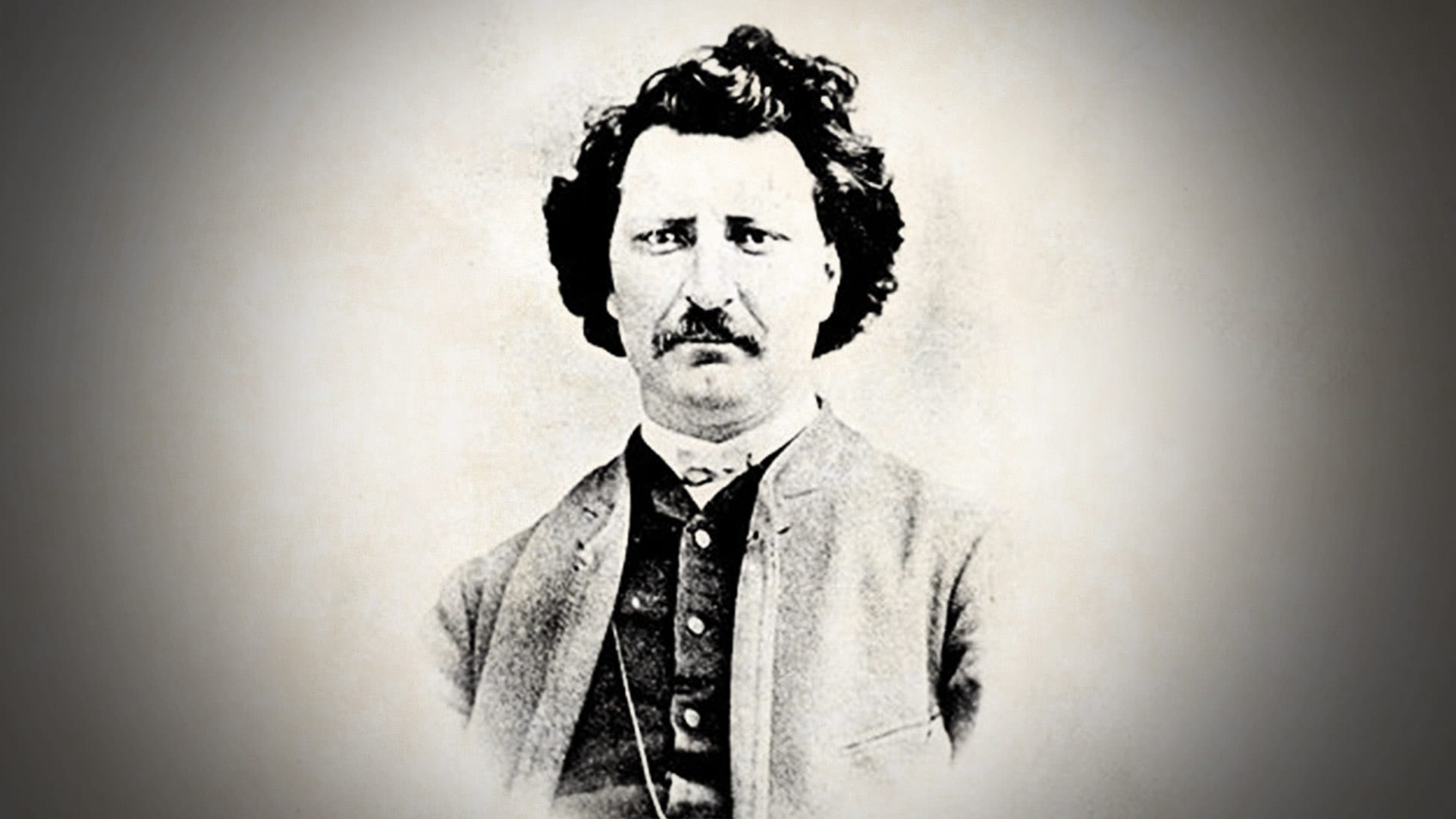

Jean Teillet remembers the day she and a couple of friends planned to snag the rope that hanged Louis Riel from its display in Toronto’s fake castle, Casa Loma.

“We were going to liberate the rope that the Royal Canadian Mounted Police were parading around that hanged Louis Riel,” says Teillet, a Métis lawyer and the great grand-niece of Riel.

It’s unclear why the rope was at Casa Loma, which is now operated by the City of Toronto.

There are many stories of the rope, pieces of which many RCMP officers and members of the public alike have claimed to own.

Back in the 1990s, Teillet was outside of famed civil rights lawyer Clay Ruby’s house with Tony Belcourt, another Métis lawyer, and activist.

They had with them a few cloth bags.

“My partner, Rick Salter, just took one look at me and he said ‘I don’t want to know what you are up to,’” says Teillet.

But she says Ruby was curious.

According to Teillet, when they explained their plan to Ruby, who has since passed away, he was interested.

“He said ‘I think that would be a great case. Who has got the right to have the noose that hanged Louis Riel, the RCMP or the family? I’ll take that case,’” says Teillet.

The rope was in a small cabinet. The plan was to bring a screwdriver to open the lock and drop the rope out the window into the cloth bags and carried away.

But by the time they got to Casa Loma, the rope was gone.

Teillet says it bothered her that the RCMP would display the item, seemingly as a sort of conquest over the Métis leader, who was hanged as a traitor in 1885 at the North West Mounted Police barracks in Regina, Sask.

As the RCMP celebrates its 150-year anniversary, Teillet’s story shows the inherent conflict between Indigenous communities and Canada’s federal police force.

The Creation of the RCMP

According to the RCMP website, they consider the creation of the Northwest Mounted Police on May 23, 1873 to be the anniversary of the RCMP.

“For 150 years, the RCMP has protected Canadians from coast to coast to coast by acting with integrity, demonstrating compassion, and serving with excellence,” says Marco Mendocino, minister of Public Safety and the federal politician responsible for the RCMP.

“In marking this anniversary, the RCMP is reflecting on its past with humility, recognizing that in 150 years there are a lot of accomplishments to be proud of, while also acknowledging that the RCMP has played a role in some of Canada’s most difficult and dark moments.”

The Mounties are as much a part of the founding folklore of the country as the Rocky Mountains, maple syrup and hockey. The Canadian Encyclopedia calls the police force “one of Canada’s most iconic national institutions.”

Early Canadian literature depicts the NWMP/RCMP as heroic young men often through semi-autobiographical work like “Trooper and Red Skin” diaries, published in 1889 by a former North-West Mounted policeman, John. D. Donkin.

“The Indian teepee; the scattered tents of the mounted police or perhaps. The log-house or sod shanty of some adventurous pioneer are the only vestiges of human life out in these mighty solitudes,” wrote Donkin of his trips in the prairies.

Steve Hewitt, who has written two books about the Mounties says in his book “Riding to the Rescue: The Transformation of the RCMP in Alberta and Saskatchewan” that the “dominant public perception of the Mounted Police is very much a nineteenth-century creation.”

“The way the mythology is presented is that [the RCMP] are neutral arbiters between Indigenous peoples and settlers,” Hewitt told APTN News.

An Indigenous perspective does not consider the RCMP, or its predecessor, the Northwest Mounted Police, to have acted as a neutral party, says Teillet.

“The side they [the RCMP] have stood on has never been about rescuing, saving, or helping Indigenous people,” she says.

The scarlet police force

American newspapers were fascinated with the early Canadian police force. A 1918 article in the De Moines Register writes breathlessly about the news that Canada’s “scarlet riders are off to the war” after “not enough to do” in their home country.

“It has been said by the early settlers who owed to the mounted police their immunity from raids by the Indians and bad men.”

To Indigenous people, the legacy of the RCMP has never been one of squeaky-clean police force with a reputation of being people who “always get their man”.

“I think it is in crisis. I think it has been in crisis for a while,” Hewitt says.

Hewitt says some issues within the RCMP point back to their creation.

“John A Macdonald [Canada’s first Prime Minister] was looking for a model and the model was a paramilitary force created by the English to basically control the Irish.”

From the days that Colonel Wolseley’s men marched westward in the first infantry regiment of Canada, there has been a tie between land rights, property disputes, and the RCMP’s interactions with Indigenous people.

“As far as my research showed me, the core group that formed the North-West Mounted Police were the same soldiers who were sent out west to inflict the reign of terror on the Métis,” says Teillet.

Triumph and dominance in Upper Canada

Donkin in his 1889 book Trooper and Redskin states that he thought Riel was “a fanatic, who having begun by taking in others ended up deluding himself.”

In other words, Donkin felt Riel was a fraudster.

Neither did Donkin hold much affinity for the Métis people themselves, who he called “ignorant half-castes [who] inherit all the love of dramatic incident, all the grotesque affection for stage effect, which is the characteristic of both their Gallic and redskin ancestors.”

Teillet says this sort of attitude towards Indigenous people was not uncommon in a force where two-thirds of the members were Orange Lodge members.

“The Orange Lodge is a flat out white supremacist organization. It is not hidden…their stated agenda was to put white protestant men in all positions of power.

“They [the Orangemen] particularly hated the Métis. They had three strikes against them. They were too Catholic, too Indian, too French,’ says Teillet.

The Loyal Orange Association, also called the Orange Lodge, still exists today as a benevolent organization that, among its other stated missions, pledges to “actively support the Canadian System of Government,”

“Those are the men who came out west with Wolseley’s troops, and those are the men who signed up to be part of the Northwest Mounted Police,” says Teillet.

Cypress Hill Massacre

Wolseley’s troops were a result of the Cypress Hill massacre. When a famine pushed a group of Nakoda toward Cypress Hills in Saskatchewan hunters in the area killed 20 men women and children from the Nakoda.

It wasn’t until August, though, when news of the massacre reached Ottawa, that an Order-in-Council was actually signed to establish the NWMP.

A year later, 300 recruits marched westward to tame the frontier.

“In the course of the march they murdered at least nine people. They did arsons, home invasions, and rapes,” said Teillet.

Inuit relocation and sled dog killing

The RCMP’s “reign of terror” has extended far beyond the Métis. In 1953 and 1955 the RCMP helped move Inuit families to Resolute Bay promising abundant wildlife and improved living conditions in the remote Arctic.

Samwillie Eliasialuk gave emotional testimony to the Aboriginal Affairs committee in 1990, saying “the women were used for sex purposes (the RCMP) would give us food. I remember this very well even though I was very young at the time.”

The RCMP also denied allegations that thousands of sled dogs had been killed by their members.

In the North an ordinance was passed that prevented dogs from running free. Sled dogs, or qimmit are very important to a traditional Inuit way of life for transportation and hunting.

The new ordinance allowed police or hunters to shoot sled dogs who were not tethered.

The Qikiqtani Inuit Association gathered interviews from 350 Inuit during the Qikiqtani Truth Commission that showed a lack of respect for the traditional ways of keeping qimmit.

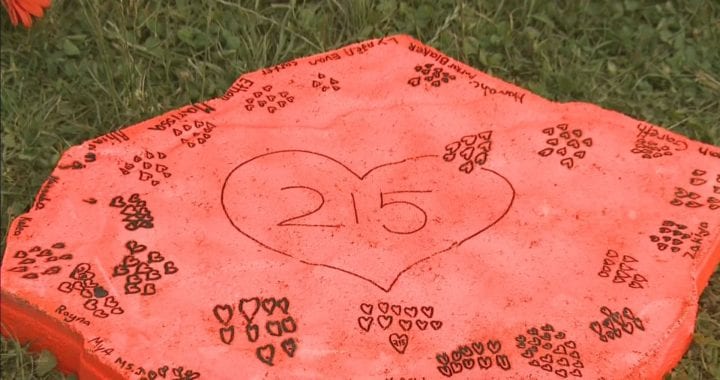

Truancy Officers

In 2011, the RCMP issued a report about their role in the Indian Residential School System.

The 470-page document finds that their participation as truancy officers (searching for students who left the school and issuing fines to parents who did not send their children to school) led to a lack of trust in their police force among Indigenous people.

The service also compromised its own investigation into abuse at residential schools.

The 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report talks about the independence of the RCMP being compromised during the E Division (British Columbia) Task Force to investigate allegations of abuse in British Columbia residential schools.

Despite widespread allegations of abuse at residential schools, the TRC was only able to find fewer than 50 convictions. This is a stark contrast to the nearly 38,000 claims of sexual and serious physical abuse set up under the settlement agreement for survivors of residential schools.

The RCMP handed over its investigation files about Kuper Island school to the federal government “without due regard for the privacy rights of the complainants in the case,” reads the TRC executive summary.

“The RCMP’s own report suggests that the E Division Task Force viewed physical assaults against Aboriginal children as being less serious than sexual abuse.

“The RCMP attributed complaints by former students about assaults as evidence of a “culture clash between the rigid, ‘spare the rod, spoil the child’ Christian attitude, and the more permissive Native tradition of child-rearing.”

RCMP and social movements

The paranoia of the RCMP and preoccupation with social movements was still obvious in 1972, when the RCMP security service burned down a barn when they suspected Quebec separatists had planned to meet with the Black Panthers from the United States.

The RCMP were also involved in what is commonly called the 1990 Oka Crisis, when the Sûreté du Québec, a provincial police force, coordinated with the RCMP during the 78-day standoff against Mohawks at Kanesatake who blocked a road to protect a burial ground from a golf course development.

Hewitt says the RCMP was deeply concerned with Indigenous rights activists after Oka.

“The so-called ‘Red Power’ movement…there was real concern about links between Indigenous activists and Black Panthers in the US,” says Hewitt.

Western Canada Symbolism

“I was born in Kitchener and the Mounties weren’t really anything…it was only when I moved to Saskatchewan where Regina had the museum and the Depot [where RCMP officers train]—that symbol was so much more powerful in Western Canada,” says Hewitt.

Teillet says numerous reports have shown issues with the RCMP’s conduct and she believes that a lot of the biases that they have been criticized for have been there since the beginning.

“My theory has always been that when we look at the misogyny and racism that report after report after report says is embedded in the DNA of the RCMP—I see it got baked in right from the beginning,” says Teillet.

She says the military leaders who helped form the RCMP brought in their prejudices, including those focused against Indigenous rights and sovereignty.

“The Supreme Court justices, some former, have said the RCMP cannot fix itself and I think it is because of that DNA,” says Teillet.

A report in 2020 from former Supreme Court justice Michel Bastarache detailed 634 interviews that showed a systemic, brutal treatment of women who entered the force.

“It is impossible to fully convey the depth of the pain,” Bastarache wrote.

RCMP Bombing

In March 1976, Robert Samson, a member of the RCMP Security Service, went on trial for charges arising from the bombing of a supermarket executive’s residence.

During this trial, Samson revealed that he had been involved in other questionable activities for the RCMP in addition to the bombing, that much of his police career had been spent breaking the law – on orders from his superiors – and that he was just one of several who had done so.

In 1999, during a trial against Wiebo Ludwig and Richard Boonstra, the Crown prosecutors admitted to information that the defense submitted evidence that Mounties bombed an oil plant as part of a “dirty tricks” campaign in their investigation into sabotage in the Alberta oil patch.

Commission of Inquiry

In 1981, after Samson’s trial, the government of former prime minister Pierre Trudeau ordered a Commission of Inquiry Concerning Certain Activities of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, more commonly known as the McDonald Commission.

The McDonald Commission brought to light many concerns with RCMP operations.

The commission recommended the police be required to obey the law and that judicial authorization should be established before the police could open citizen’s mail.

The report was never tabled in Parliament.

Costal Gas Link

In 2020, the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs, Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs, and BC Civil Liberties Association wrote a letter to the Civilian Review and Complaints Commission or CRCC for the RCMP about an exclusion zone the Mounties had set up around Wet’suwet’en territory.

That’s where supporters of the hereditary chiefs had set up a roadblock to stop the construction of a pipeline through the territory.

The CRCC pointed to previous findings from earlier commissions.

“There is absolutely no legal precedent nor established legal authority for such an overbroad policing power associated with the enforcement of an injunction.

“The implementation and enforcement of the RCMP exclusion zone in Wet’suwet’en territory is unlawful,” says a letter by BC Civil Liberties.

In June 2022, APTN reported the federal watchdog received nearly 500 complaints from the Wet’suwet’en operation in B.C., but only five led to disciplinary actions.

The RCMP also put together a secret unit called the C-IRG – Community-Industry Response Group to ensure that resource projects like the Coastal GasLink isn’t interfered with by Indigenous opposition.

Death of Colton Boushie

A young man named Colton Boushie, 22, was shot and killed by white farmer Gerald Stanley in August 2016.

Boushie’s friends had driven onto Stanley’s property while Boushie was asleep in the car. After an argument, Stanley fired three shots. One of them struck Boushie.

A jury acquitted him of second-degree murder.

In the aftermath of the verdict, many community members took to protesting the trial as well as the RCMP’s handling of the investigation.

The CRCC identified deficiencies in the investigation such as a mishandling of evidence and witnesses.

The report also found that Debbie Baptiste, Colton’s mother had been racially discriminated against when the police notified her of her son’s death.

The police watchdog also found that an early RCMP media release about the shooting could have left the impression “that the young man’s death was ‘deserved.'”

A Globe and Mail investigation also found that the RCMP “destroyed records of police communications from the night Colten Boushie died.”

Mass causality events

In 2004, four members of the Mayerthorpe RCMP detachment in Alberta were killed. Justice Pahl completed a report called The Mayerthorpe Review in 2011. It recommended that “the RCMP consider the establishment of national policy guidelines for the securing of potential crime scenes”.

After a shooting in Moncton, N.B. in 2014 that left five dead—three of them members of the RCMP— there was an independent report that called for training “to better prepare supervisors to manage and supervise throughout a critical incident until a [Critical Incident Commander] takes control.”

The 2014 report noted that Moncton RCMP was unaware of the guidelines suggested after the Mayerthorpe deaths.

In 2020, another mass casualty event in Nova Scotia led to an inquiry into a scathing report about RCMP operations.

In particular, the report took aim at the RCMP response to the crisis. It called out a lack of preparation, poor communication, and leadership.

The issues were so prevalent and systemic that the commissioners called for the RCMP to rethink how the entire force operates.

Today, the RCMP is still the subject of multiple human rights complaints.

Transparency and Trust

On May 18, the RCMP released its transparency and trust action plan.

“Public trust in policing has decreased. The RCMP is taking action to be more open and transparent while building and strengthening trust in law enforcement,” says the news release.

Trust in the police does seem to be on the decline.

Statistics Canada reports that only 41 per cent of Canadians had “great confidence” in the police in 2019. Another 49 per cent have “some confidence”.

Visible minority groups and people with disabilities as well as victims of crime, expressed lower levels of confidence.

Today, the RCMP plan around transparency is focused on the release of information on “police intervention options,” calls for service and employee and diversity statistics.

Their strategic plan also aims to reduce bias and “advance Indigenous reconciliation”. The plan does not go into specifics.

Hewitt says it is time to consider what role the RCMP should now play in Canada after 150 years.

“To have a paramilitary force perhaps made sense in the 19th century. I am not sure it makes sense in the 21st century. I think they need reform…all the scandals around sexual harassment and assault.

“But the Mounties, because they are this national symbol, make it difficult to reform,” says Hewitt.