On an oppressively hot and humid evening with storm clouds hanging overhead, Melanie Morrison leads about three dozen people down Hwy 132 in Kahnawà:ke Mohawk Territory, just south of Montreal.

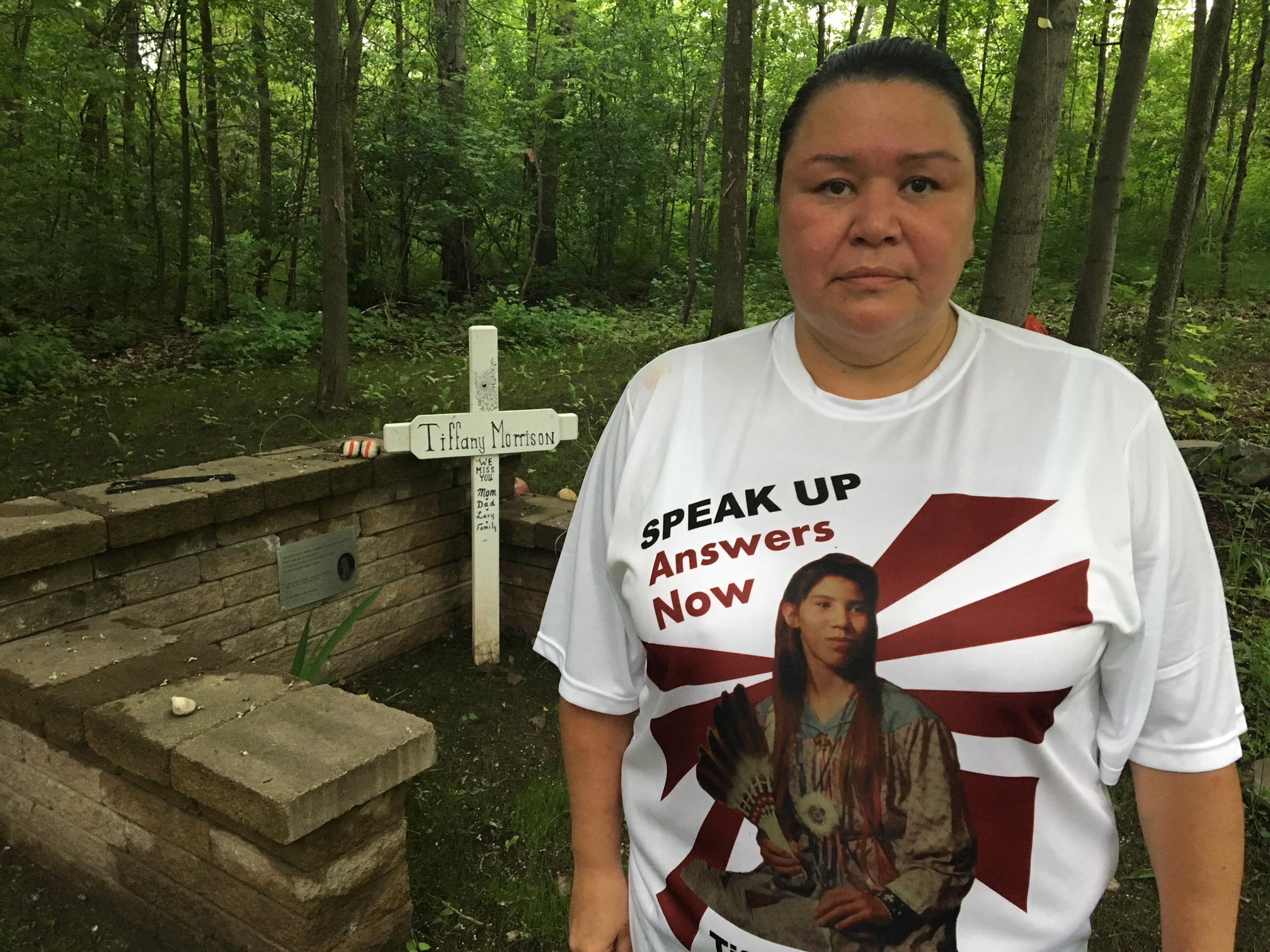

“Speak up, answers now, justice for Tiffany Morrison,” Morrison shouts, her face flushed. A deep red emerges with every bellow, then recedes a little with every inhale.

“Every year we have horrible, horrible heat,” she says. “I say it’s Tiffany’s way of making us work.”

The 44-year-old Mohawk and Mi’gmaq woman leads the group through service roads adjacent to traffic towards their eventual destination, the wooded area where the body of Melanie’s sister Tiffany was found eight years ago.

The marchers echo Melanie’s shouts for justice and angle their banner towards the highway so the evening traffic can see its slogan.

This march is an annual affair and very little organzing is needed.

Many here know the route, know the tradition and most of all know the date.

June 18, 2006 – the day the 24-year-old vanished.

The night Tiffany went missing she was at a bar in LaSalle, a Montreal neighbourhood that is less than a ten-minute drive across the St. Lawrence River to Kahnawà:ke.

She got into a taxi with a fellow community member and the cab drove them back to Kahnawà:ke.

Tiffany never made it home.

According to Melanie Morrison, the man Tiffany shared the cab with got out first.

“He is the last person to see her,” says Morrison.

“He said he'd take a lie detector test, then four days before he bowed out for religious reason, saying his longhouse wouldn't let him.”

Kahnawà:ke police say he was a suspect - but now that the file has been transferred to the Surete du Quebec (SQ), and it's not clear whether that is still the case.

The cab driver was also a person of interest but has never been identified.

Morrison blames the Kahnawà:ke police, known as “Peacekeepers”, saying they were not properly trained at the time to handle a missing person's investigation.

“The initial taking of the missing person's file, the info, 'she might've just went out drinking, she's young,'” says Morrison, frustration still apparent in her voice.

“But we stated to them she wasn't like that because of her daughter, if she was going to change plans she would've called my mother.”

For four years Tiffany was classified as a missing person.

Then on May 31, 2010, a construction worker found Tiffany’s remains only a few kilometres from her home.

The discovery left the Morrison family distraught in more ways the one.

Morrison says Peacekeepers had discouraged the family from organizing their own community searches to compliment police searches.

“When I asked if searches could be done, they said we could contaminate things, it would be best if we wait for some sort of evidence so we can do a proper search,” says Morrison.

After the discovery of Tiffany's remains the case was classified as a homicide, meaning the SQ would take over.

It took a year to transfer the case to SQ investigators.

“People had to be called in to back for statements because they hadn't taken statements,” says Morrison.

Yet despite her past criticisms, Morrison said she currently has a good relationship with the Kahnawà:ke Peacekeepers.

They have asked her to speak to other Indigenous police forces and she takes cold comfort that things would likely be different if someone were to go missing in Kahnawà:ke today.

Melanie pushed to have a better protocol for officers in terms of how they take missing person's reports, as well as training so it doesn’t take a year for the Peacekeepers to hand a case over to a larger force such as the SQ.

When contacted for comment, Peacekeepers Assistant Police Chief Jody Diabo confirms that should a person go missing in Kahnawà:ke today, things would be done differently.

This is the kind of institutional change that Melanie Morrison has been fighting for in the years since her sister's murder.

“We can hope that this never happens to another family and that they're given the right information, that they know what they can do when it comes to a search,” she says.

In May of 2017, she was recognized with an award by Amnesty International for her advocacy and has served as a part of the family advisor circle for the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Woman and Girls (MMIWG).

Yet despite her involvement and outspokenness, Morrison was advised not to testify at the inquiry because it could affect Tiffany's case.

“I'm at peace with that,” said Morrison, who declined to say who's advice it was to avoid the larger stage of the national inquiry.

“With me being able to still voice my opinion in what needs to change in the process, I'm still doing good by my sister and for all the women that have gone missing or been murdered.”

The marchers turn off Hwy 132 and enter the woods.

“Speak up, answers now, justice for Tiffany Morrison,” they shout even though they no longer have an audience.

A memorial to Tiffany lies in the shade of several trees, close to where she was found.

Melanie has described Tiffany as having boundless energy with an infectious laugh, the sort of person who could pick you up if you're feeling down.

Her memorial is in contrast to that, a somber place of solitude.

The marchers gathered round, touch the wooden cross bearing Tiffany's name, say an unspoken prayer.

The wind from the approaching storm shakes the leaves, the occasional nervous birdsong is almost loud enough to drown the sound of the nearby highway.

A Mi'gmaq honour song is played out of respect for the paternal side of the Morrison family.

Melanie thanks the marchers for coming and vows to be back next year.

“It doesn't matter if it's just her family, or ten people or two people behind us, we're going to be out here raising awareness. Tiffany is still waiting for justice, and as long as she's stuck, we fight,” she says.

The crowd makes its way back to their cars just as the skies open up.

The downpour that follows is heavy and relentless.

“Tiffany is playing an evil joke on us,” Melanie says with a laugh. “That's her humour, let us think we got away with it then douse us at the end.”

Humour helps Melanie get by on every June 18.

The rest of the year, it's the knowledge that someone somewhere knows what happened to Tiffany that drives her.

There is a $75,000 reward for information leading to an arrest in the case of Tiffany Morrison. Anyone with information can call the Kahnawà:ke Peacekeepers at 450-632-6505