Editor’s Note: This story contains graphic content that may not be suitable to all readers.

Cullen Crozier

APTN Investigates

George Munroe carefully sets out his smudging medicine on the kitchen table, handling each item with practiced care and reverence.

“When they brought in the church you had to start going to, I think they called it catechism, every day at four o’clock to the church,” Munroe says as he gently lays out two braids of sweetgrass, a bundle of sage and a small pouch of tobacco.

“And me, I was taught to be an altar boy and this is where the abuse started.”

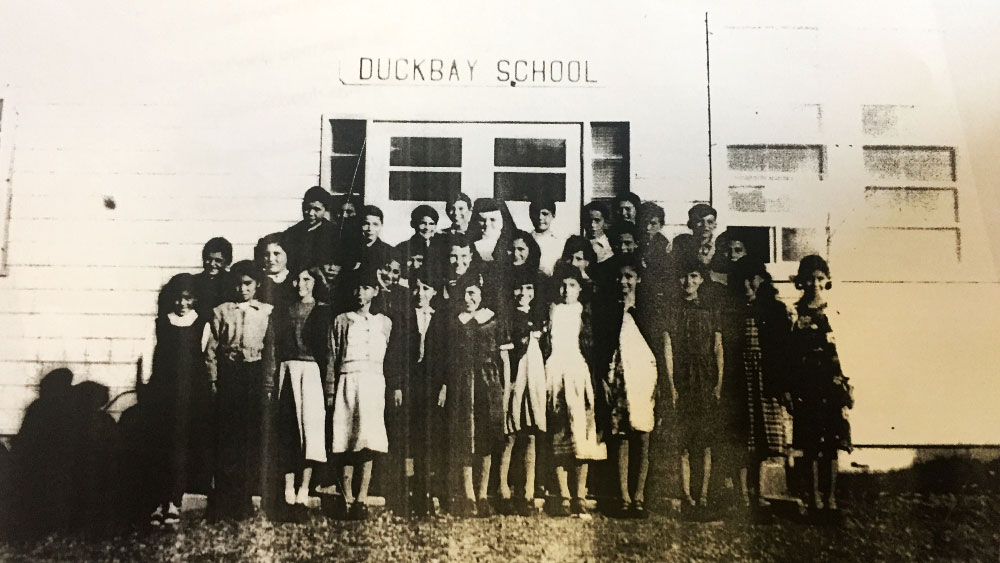

(Children standing in front of the Duck Bay Special School number 2163 circa 1965)

The 74 year old Anishnaabe Elder strikes a wooden match and slowly lights a small pile of tobacco and sage.

He stands over the smoke and starts taking it in – his eyes closed in deep reflection.

“There was quite a few of us trained as altar boys,” Munroe continues. “But nobody ever talked about what happened.”

“The abuse that I experienced was always private. Like I say, I was a Catholic boy, an altar boy so they have their private rooms where masturbation took place, anal penetration, rape, whatever you want to call it, that took place. But we never talked about it because we were ashamed.”

(George Munroe smudging at his home in Winnipeg, MB. Photo: Cullen Crozier/APTN)

Munroe grew up in Duck Bay, Manitoba, a small Indigenous community on the western shore of Lake Winnipegosis.

He spent most of his time on the land learning to hunt and trap with his father.

But all that changed when the church came to town.

Built in the early 1950s, the Duck Bay Special School number 2163 was run by the Roman Catholic Church and just like the residential schools of the day, the ultimate goal was assimilation and genocide.

“The school was bad, the abuse was bad, the nuns were involved, the priest was involved,” Munroe says. “They’d take boys to church, the men priests would take the boys and the nuns would take the girls.

“I don’t know what happened there but according to their stories they were abused the same way.”

(George Munroe holds a picture of the old Duck Bay church. It’s where he remembers first being sexually assaulted – he was only seven. Photo: Cullen Crozier/APTN)

The Duck Bay School is what’s known today as a day school, meaning the children were allowed to return home at the end of each day – back to their families. But in many cases they were either too ashamed or too afraid to tell their parents what they experienced.

It was a vicious cycle of abuse that former students like Abraham Parenteau remember all too well.

“That’s where I got physically abused at that school,” Parenteau says from his home in Winnipeg, Manitoba. “I didn’t want to tell anybody, nobody knew, not even my parents knew. And I was ashamed because of what they did to me.”

According to former students like Parenteau, the abuse was severe. He remembers children being strapped with a thick piece of rubber transmission belt. While others were tied up outside with dog leashes as a form of punishment.

“Either abused physically, mentally, sexually, you name it,” Parenteau recalls. “The same thing that happens with the Indian Day Schools, the residential schools, we were treated the same way – no difference.”

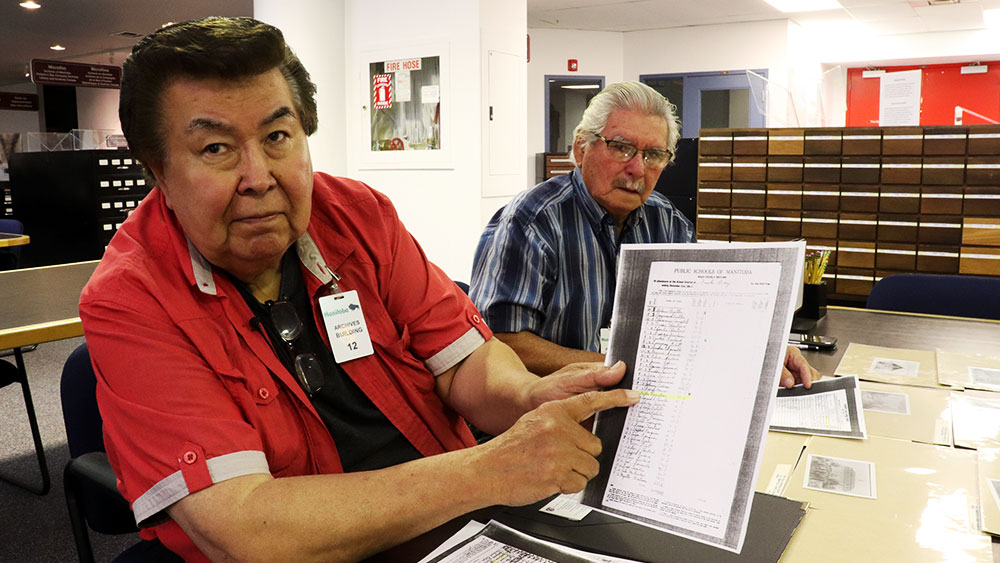

(Abraham Parenteau finds his name on an old school attendance record. Photo: Cullen Crozier/APTN)

For decades now, former students like George Munroe and Abraham Parenteau have been seeking justice for Indian day school survivors across the country. And earlier this year it looked like they would finally receive recognition and compensation for the abuses they suffered.

In August of 2019, the Federal Court approved a $1.4 billion settlement for Indian Day School survivors.

Up to 140,000 former students are eligible for compensation, with more than 700 institutions officially recognized – the Duck Bay School was not on the list.

“How can you have reconciliation and justice in Canada if half of the abused people that have been abused and raped are not recognized?” says former day school student, George Munroe.

“Including the people in the sanatoriums, the people that went to the reform school and the people that went to private school, that were all run by different church organizations.”

All told there are more than 680 institutions that were left out of the Indian Day School settlement agreement. And the reasons vary.

The most common being that the schools were funded or operated by others such as provincial governments or with Duck Bay – religious organizations.

“They told us that we were not eligible,” says former Duck Bay student Abraham Parenteau. “So, since that time, we’ve been fighting to be recognized and to tell our story of what happened. And to let the whole of Canada know exactly what we went through.”

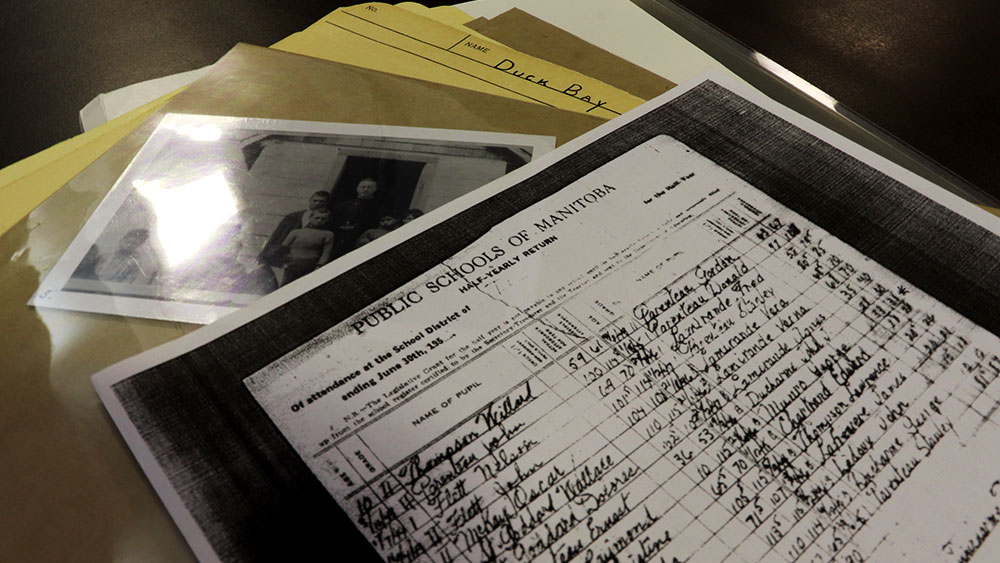

(Photographs and documents of the Duck Bay Special School number 2163, found at the Provincial Archives of Manitoba. Photo: Cullen Crozier/APTN)

Even though the Duck Bay School was run by a church organization, given that it operated for decades in an Indigenous community, it’s hard to believe that the federal government didn’t have some form of involvement.

But finding that physical evidence comes with its own set of challenges.

After they were informed that their school was one of more than 680 institutions excluded from the Indian day school settlement, Munroe and Parenteau decided to take matters into their own hands.

The two Anishnaabe Elders have spent many hours searching for proof of federal involvement. Meticulously combing through hundreds of records and files housed at the Provincial Archives of Manitoba in downtown Winnipeg.

The most they’ve been able to come up with are old attendance records and photographs of the Duck Bay church and school house.

Along with their research efforts, Munroe and Parenteau have also formed an organization made up of other survivors who were excluded from the Indian Day School settlement.

“We formed up an organization called the Unvalidated Day School Society of Canada,” Parenteau says. “We are fighting to get these other people compensated from the wrongdoings that the government has imposed on them when they excluded us from that process.”

(Anishnaabe Elders, George Munroe and Abraham Parenteau look at a picture of the Duck Bay Special School number 2163. Photo: Cullen Crozier/APTN)

This past September, Munroe and Parenteau travelled back to the community of their youth.

Duck Bay has changed little over the years and it didn’t take long before the memories started rushing back into focus.

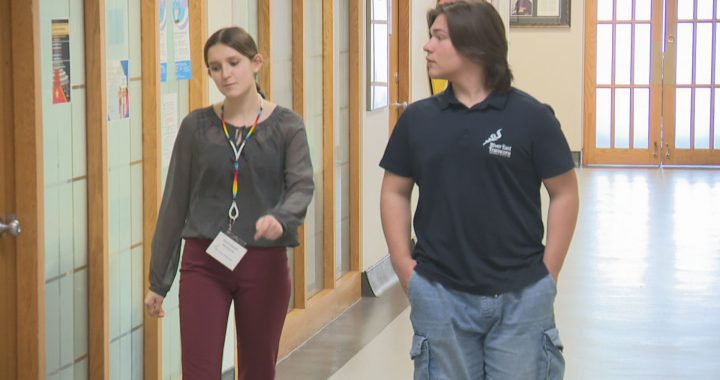

The Duck Bay Special School number 2163 has long since been torn down. Built in its place is the new Duck Bay community school. But for Parenteau and Munroe, the memories of the abuse they suffered and witnessed there still haunt them.

“This is where all the restrictions took place and this is where a lot of people got punished,” Parenteau says standing in the yard of the new community school. “This is where I got punished – physically abused.”

“Straps, rulers, yard sticks,” adds Munroe. “They used whatever they could get a hold of to beat us up.”

(Old Duck Bay church. Photo: Manitoba Archives)

Just across from the school sits an open field, once home to the old Duck Bay Church. It’s where George Munroe first remembers being sexually assaulted – he was only seven.

“It’s a little difficult for me because of what happened to me in this building and the abuse by the man of the cloth, that’s supposed to protect us and he’s the one who raped us and abused us,” Munroe says holding up a picture of the old Duck Bay Church.

“I feel it every time I come to a funeral of one of my relatives or somebody that passed away, that we have to put away because of what happened in this building. So it’s kind of emotional for me.”

Duck Bay is a small tight knit community and family ties here run deep. Parenteau and Munroe were in town for less than an hour, but word quickly got around, and a number of community members, former students of the Duck Bay School, joined them to share their stories.

(Anishnaabe Elder, Abraham Parenteau holds up a picture of an old log cabin that was used to teach the children of Duck Bay, Manitoba. Photo: Cullen Crozier/APTN)

“I use to work a lot for the nuns, like haul water and that,” says former Duck Bay student Ernie Parenteau. “Then one time I accidentally knocked over the statue, Blessed Virgin Mary and then they really got mad and they burnt me.”

Parenteau held up his hand to show a small circular scar.

“I don’t know what they burnt me with that time because one of the nuns had her hands covering my eyes.”

“We had that pretty near every week or sometimes every day – straps,” recalls former Duck Bay student Clifford Parenteau. “The nuns they had two straps, one was red and one was black. If they didn’t make you cry on the black one, they’d use the red one. And the red one was a real stinger.”

“I was nine-and-a-half years old. He would have sex with me and he told me, when I get older I would like this,” says former Duck bay student Violet Guiboche, as she reads from a letter she wrote detailing her abuses. “He would take me out of the school at three o’clock PM, along with the other girls and take us to the church to sexually abuse us.”

(Anishnaabe Elders George Munroe and Abraham Parenteau standing along the shore of Lake Winnipegosis. Photo: Cullen Crozier/APTN)

As the sun starts to set on the community of Duck Bay, Parenteau and Munroe still have a long journey ahead of them.

“I was a victim, I experienced all of the things that they were doing,” Parenteau says. “And that’s why I wanted to share my story, is to let the people know now and I didn’t want to continue hiding what happened to me.”

The two men aren’t sure where the road will ultimately lead. Only that their battle for recognition is just beginning.

“I don’t know how we are going to correct this,” Munroe says. “I know there is a lawsuit going on, but how can the government of this country talk about reconciliation if the class action that’s being presented today only has 700 schools? So where’s the justice?”

@cullencrozier

Can Day school survivors who are left out, who opted out or who don’t agree with the settlement pursue legal action and settlement on an independent basis?

Yes I believe these men… the priest and nuns made sure that the blame of this crime of rape… was put straight onto the victims… to make sure that this was the only way… the victims saw themselves as… and it was all done in the name of god… at the same time the Shame of these crimes… was also what these men had to carry around with them… take a look around the world in every country… there you will see and read about… some sort of damage which the catholic church nuns and priest did to the children = boys and girls… who they should have looked after… I hope that these men get Justice for these crimes… of the catholic church nuns and priest…

I m one of the students in the Duck Bay school picture,