Warning: This story is based on interviews with survivors of sexual abuse.

For Valerie Fisher, it was a simple life with her family on Crooked Pine Lake on Treaty 3 territory in northwestern Ontario.

Swimming in the lake, the mist in the early mornings and the storms.

She picked wild berries and flowers.

“I felt so connected to the land, I felt that life force,” says Fisher. “Those were the best years of my life.”

It was short-lived.

At the age of six, Fisher says her mother dropped her off at St. Margaret’s Residential School in Fort Frances, Ont.

She did three years there.

In that time, her mom and dad had left the lake and moved to Rainy River First Nations near Fort Frances, Ont.

When she came home for good three years later, nothing was like she remembered; her parents often threw parties on the weekends that turned ugly.

“I witnessed [my mom] being violently raped a number of times when I was a small child,” says Fisher, now 66, and eldest of seven children.

At the age of 12, Fisher’s life changed forever when she offered to walk a drunk man home in the early morning hours.

When they got to his house, she put him to bed.

“That’s where he raped me, sexually assaulted me,” she says, breaking down in tears.

“I somehow rolled off the bed and I grabbed my jeans and put my shoes on and I sort of staggered out the door.”

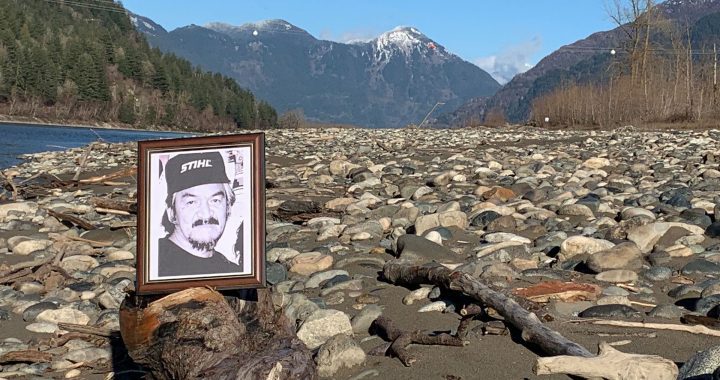

Fisher says her abuser was David Debungee, who passed away in 2008 at the age of 68.

He was in his early 30s.

She was just a child.

Shattered.

And instead of getting help, her family blamed her.

“My uncle Ronald called me a whore, a 12-year-old. My mother said I wasn’t innocent anymore. It was my fault.”

Fisher says the community shamed her.

With no one to turn to, her life spun out of control.

She began drinking and running away.

Instead of seeing a kid with a broken spirit, everyone saw a problem child, according hospital records.

“I just couldn’t beat this feeling, this repulsed feeling in my body and no matter how many times I washed, I couldn’t wash that off. I thought this was all my fault. The low self-esteem kicked in and the suicidal depression. Because I wanted to die. I wanted to die,” she says, sobbing.

Fisher’s attack happened more than 50 years ago but nothing appears to have changed since.

The rate of sexual abuse across Treaty 3 territory is 10 times higher than the national average, as reported by APTN earlier this week.

And that’s just what’s reported to police.

A two-year-long investigation by APTN has found that number is likely much higher.

It’s a silent epidemic and not because no one can see it, but because not enough people are talking about it, say survivors of abuse.

So why hasn’t anything been done to address it?

Cheynna Gardner tried in early 2021.

She and a few friends lit a sacred fire to call out sexual violence in her home community of Eagle Lake, approximately 130 kilometres east of Kenora, Ont.

“Most people that I know, like my friends that are my age, a lot of them have gone down a path of addiction. Every single one of them was sexually abused by family or relatives,” says Gardner.

Instead of receiving support from the community, Gardner says the group was harassed on social media by fellow community members who wanted the fire to go out and the truth kept buried.

“Victims are further victimized in our communities when they talk about their abuse, when they want justice. We’re the ones that are looked at as being hateful and in the wrong,” says Gardner.

She says everyone in the community knows who the abusers.

“I was also sexually abused growing up by people in my community and they still walk around free when they’ve done it to not just me, but a lot of other people too. When you do that to somebody, it really, really destroys their spirit. It’s like you take something from them.”

The fire was lit for 92 days before it went out on June 24, 2021.

But before it did, Gardner also spoke to the media, including going on APTN’s Nation to Nation on May 6, 2021.

She said something at the time about the root cause of the sexual abuse that some felt was controversial.

“It absolutely stems from residential school and colonization, like I understand that, like that’s where this comes from, but at what point are just using that as an excuse to continue that behaviour?”

This was before the discovery of the unmarked graves at residential schools.

But her opinion hasn’t changed.

“I still stand behind that. I still stand behind that 100 per cent. Even with the discovery of all the children that have been, that’s been coming out in the last year, it’s devastating. It’s heartbreaking to think that this was happening to babies,” she says.

“But what about the kids in our community? What about the ones that are here still? Like, what about them? What are we going to do to protect them? It’s still happening now. We’re doing it to each other.”

Fixing that damage is easier said than done.

No amount of resources can fix something people won’t admit is happening.

The survivors that APTN spoke to for this story believes what’s happening in Treaty 3 is happening across the country.

It’s a national silent epidemic and it’s time to start talking about it because too many lives are at risk.

That’s what Carol McBride, president of the Native Women’s Association of Canada, believes.

“We have to deal with this. We have to talk about it. The status quo isn’t working. We still are losing our young people to the trauma that they suffered. And there are so many addictions and our young people taking their lives and they just lost the meaning of life,” says McBride.

“We have to help them … and we have to have start having discussions. Let’s start talking about what we’re feeling inside. I think we’ve shut it out.”

McBride says there’s many reasons why sexual abuse in First Nations has been kept quiet.

“Probably the trauma itself, they don’t want to relive it. The other thing is, is the shame. [Survivors] definitely the fear of hurting someone else with their stories. But we need we definitely need to start talking. We need to create safe places for our women and our children to be able to talk. And our men are going through the same trauma as our women. So that’s what I’m seeing and I’m hoping that the open dialogue will start helping to heal those wounds.”

McBride says Gardner’s comment about no longer excusing sexual abuse because of past trauma is a fair one.

“That’s a fair statement for sure and what I would like to see is we have the resources to be able to take back our culture and to start practicing it and having people trained to be able to help our brothers and sisters with the trauma that they experience and to keep our younger generation safe, that they don’t have to live through this,” she says.

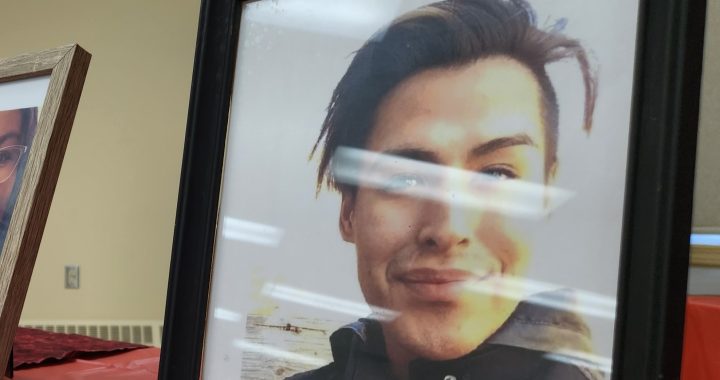

It begins with believing abuse survivors says Craig Lavand of Waszush Onigum First Nation in Kenora, Ontario.

Lavand says he was sexually abused in his community as a child and knows many survivors.

He turned to drugs to cope and was labeled a drug addict.

“If you’re going to accuse someone of being addicted, you need to address the issue like, why are they addicted? Why are they running away from home? Why are they acting out in certain ways? You know, we need to listen to the people being loud in the room and ask them why? Why are they seeking this attention?” says Lavand.

“It’s really hard to expect truth and reconciliation from the outside world when we can’t even reconcile and tell the truth in our own communities.”

He nearly killed himself a few years ago trying to end the trauma, first by driving his car into the ditch and then by trying to drink himself to death.

But he lived and began facing his trauma one step at a time.

Lavand recently returned to his community in the next step of his healing journey that continues today.

“I had to address that issue and I had to come back home and face my demons. And my demons are my abusers. And they still hold a lot of power over me,” he says.

Lavand says he plans to go to police soon and give a statement.

“I think just by pressing charges and them having some sort of accountability, that’s going to give me more healing. Because even just me coming back and talking about it, I’m starting to stand up and I’m starting to have more strength every day.”

Accountability is something everyone brings up to APTN about sexual abuse. Some people have had the courage to confront their abusers over the years, but many do not.

That’s why it’s time to light another fire.

The eighth fire, says Cheynna Gardner.

And not just for the survivors but stop the abuse from continuing.

“Light gets rid of dark. That’s the only thing that does. Bringing light, the eighth fire, the prophecy, like it’s time to light that up.

“Show what’s going on and it’s time now.”

APTN reporter Kenneth Jackson continues to investigate sexual abuse. He can be reached by calling or texting 613-325-6073.