It is often said that the truth must come before reconciliation – and in late May, on the grounds of the former Kamloops Indian Residential School, Canada was delivered a difficult dose of truth.

The impact of the ongoing confirmations of unmarked graves on former residential school grounds are continuing to unsettle Canadians in profound ways, with renewed public outrage, and calls for accountability from both the churches and the Canadian government.

However, these ancestral graves are not “discoveries,” but rather affirmations for what survivors had already known for decades.

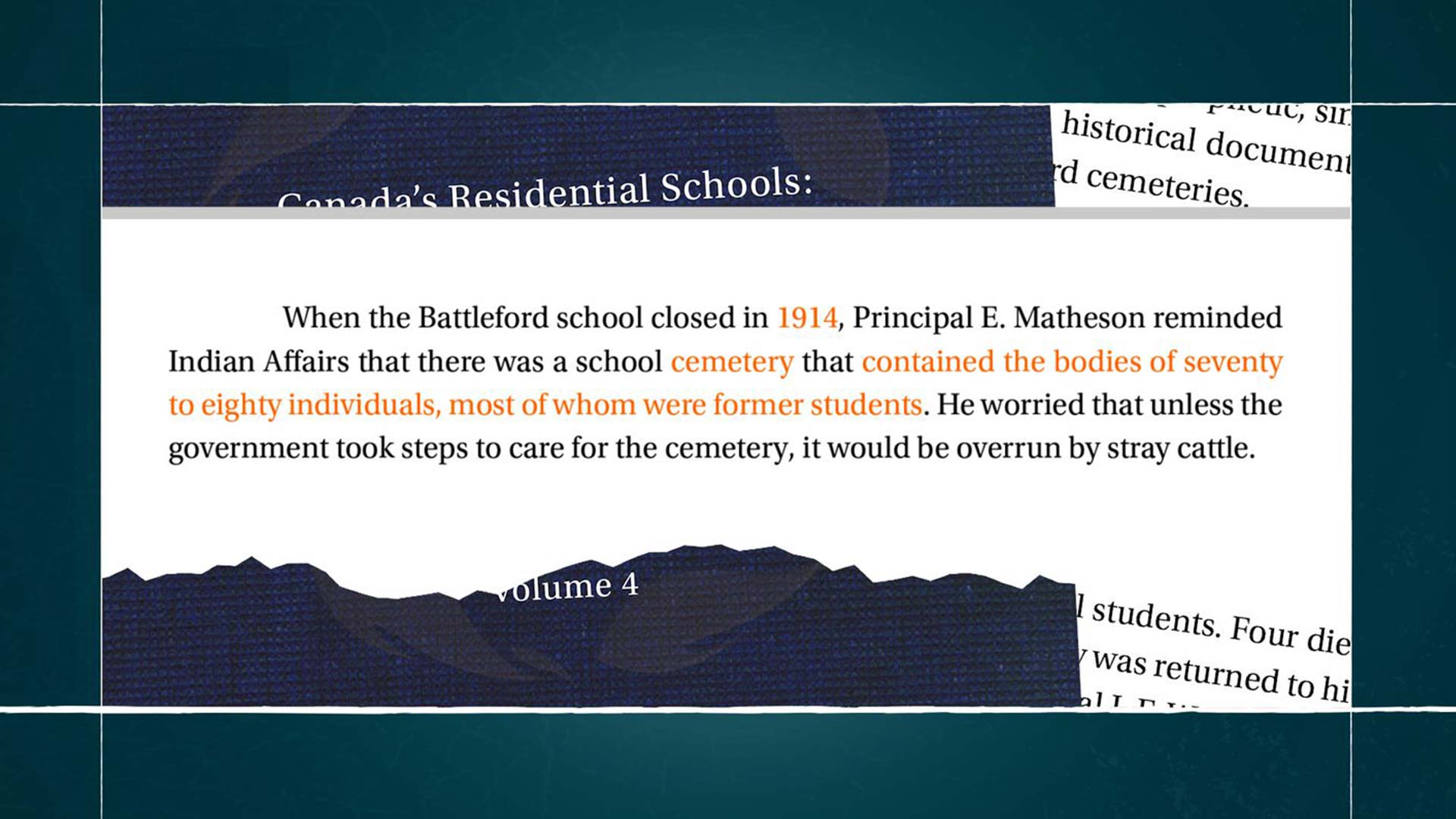

And, like survivors, the Canadian government has also known about abandoned residential school graves for generations. As early as 1914, as documented in the Truth and Reconciliation Report Volume 4, the federal government was warned about these abandoned cemeteries.

Despite this widely shared evidence, many government officials, including Minister of Crown-Indigenous Relations Carolyn Bennett, have referred to the confirmation of abandoned residential school graves as a Canadian “mistake.”

“There is no mistake about it, It was intentional,” says Veldon Coburn, assistant professor at the Institute of Indigenous Research and Studies at the University of Ottawa. “It’s easier to move to innocence when you say it was a mistake… I take more offense to the idea that the suggestion that it was a mistake, like, somebody slipped on something, and said, oops, sorry, we just killed millions of Indigenous people and we destroyed the lives of Indigenous children and societies that are going to follow afterward.”

Coburn adds that falsely framing residential schools as an isolated mistake from a well-intentioned government whitewashes the direct role they had in creating a colonial system designed to assimilate Indigenous Peoples into Canadian society.

“Canada’s role in residential schools was planned and deliberate, there’s an architecture to it there,” says Brenda Macdougall, chair of Métis Studies at the University of Ottawa. “If you take children away, you leave communities without hope and without future.

“And so, these are not schools where people were sent to become university professors or to become mathematicians or to become engineers. And if we don’t acknowledge that plan, then we can never move past it.”

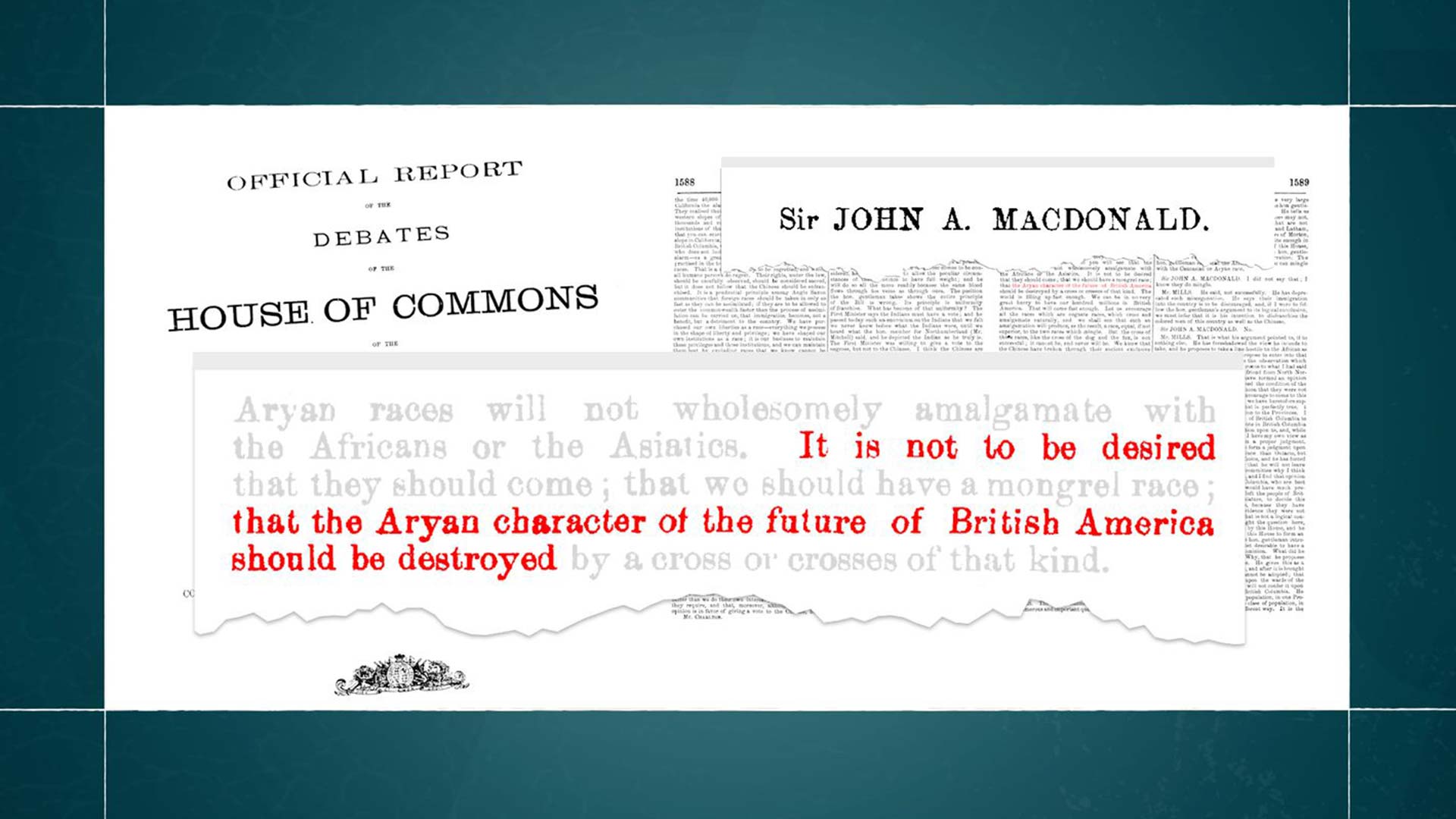

University of Ottawa historian Timothy Stanley can trace the origins of Canada’s colonial present to one of its founders: John A. Macdonald.

“He’s the only person in the House of Commons in the Senate who actually uses the term Aryan during this time,” Stanley says. “His idea is that Canada should be founded by a pure ‘Aryan’ race, and by Aryan, he means people who are racially pure and superior… a hierarchy of races of which people like him are at the top.”

Stanley’s peer-reviewed research shows that Macdonald integrated his ideas about racial superiority in a way that hadn’t been done before.

“He’s the first person, as far as I know, in the British Empire to take biologically defined notions of race and make them into law.”

But colonialism is not an idea from the history books. It’s something alive and living today. The very foundation of the house of Canada.

“Look at what happened in residential schools: they stole our children, put them into the care of someone elsewhere they were abused and many didn’t make it out alive,” says Pamela Palmater, chair in Indigenous Governance at Ryerson University.

“What’s happening in the current foster care crisis today? Stealing our children, putting them in the care of other people where statistically we know there are far less likely to graduate from high school, they’re far more likely to be sexually abused, physically abused, end up in youth corrections, end up living on the street and more likely to be incarcerated as an adult or live in poverty.

“There really isn’t a policy that you can point to from the past that doesn’t continue today, perhaps even under a different name.”

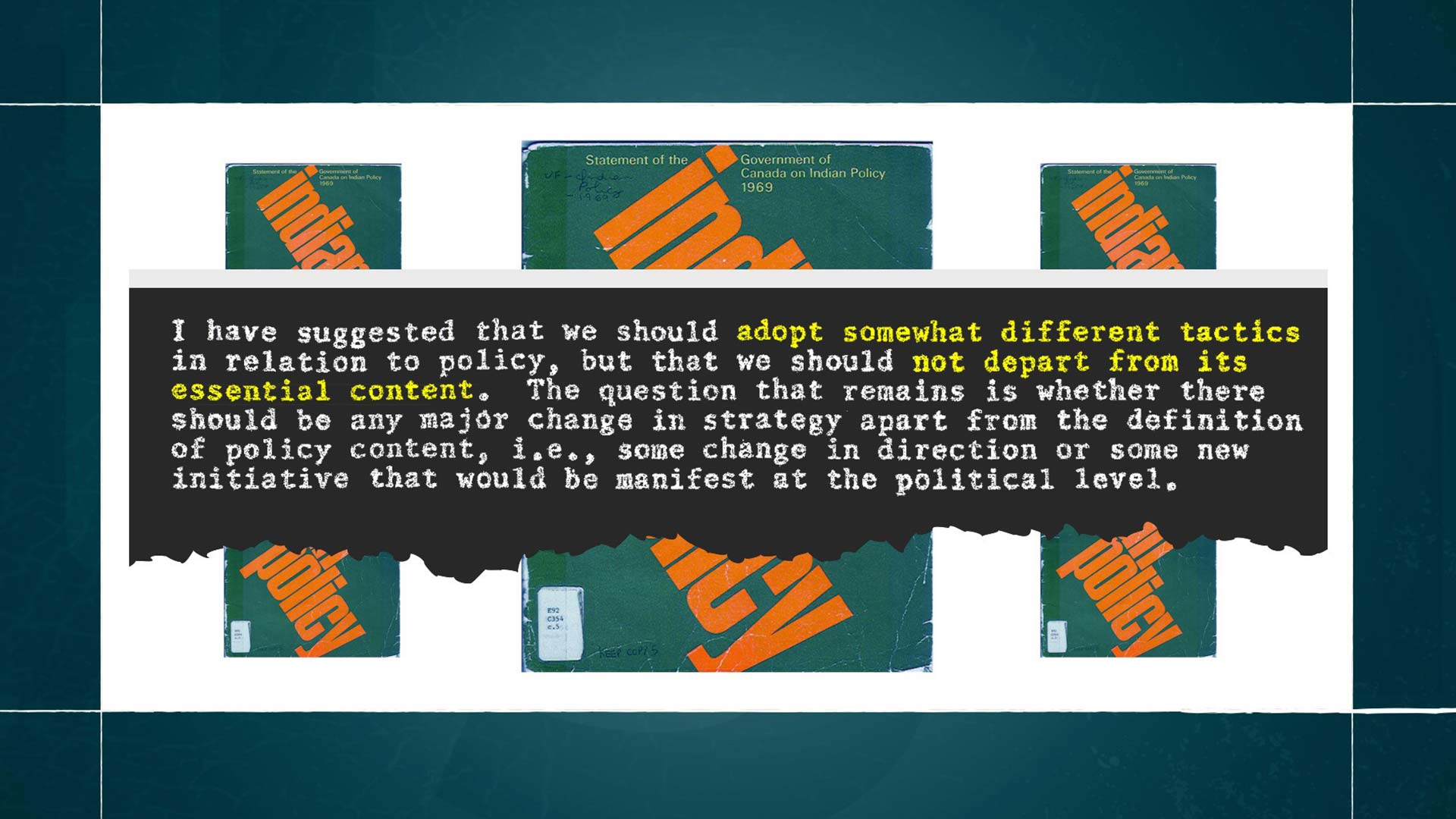

Supporting Palmater’s claim, APTN Investigates has unearthed an internal Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development memo that details Canada’s intent to continue its colonial policies against First Nations Peoples.

In a 1970 memo written by assistant deputy minister David A. Munro, he notes the “unanimously unfavourable” rejection of former prime minister Pierre Trudeau’s assimilationist White Paper, which First Nations leaders at the time called “cultural genocide.”

Despite its unpopularity, Munro proposed continuing furthering the agenda of the White Paper covertly through “a change in tactics, strategy, or policy content,” to unpack the White Paper into smaller parts, to “adopt…. different tactics” but not to “depart from its essential content”.

Canada’s colonial tactics continue to be covert in this way. According to a Queen’s University study by Susan Collis, since 2005, a list of at least 47 federal statutes and bills have attempted to circumvent the Indian Act, to control the finances, territories, rights, and governance of Indigenous Peoples.

Canada’s tactics, you could argue, are like something out of a colonial playbook. A colonial playbook designed to deny and delay Indigenous justice.

“I think that Canada is socializing its citizenry into thinking that we’re in an era of reconciliation and nation to nation but at the level of practice that is not true,” says Algonquin Anishinaabe-kwe scholar Lynn Gehl.

Dene scholar Glen Coulthard sees similar hypocrisy at play and has been at the forefront of countering Canada’s colonial playbook. His foundational 2014 book Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition shined much-needed light on Canada’s colonial politics that are designed to work against the rights of Indigenous peoples.

“When we focus on residential schools or we focus on any singular aspect of this process,” Coulthard says, “it doesn’t give the broader picture.”

He argues that Indigenous peoples need to reject the “politics of recognition,” or in other words, being satisfied or deceived by kind words or symbolic gestures without concrete action.

“When the recognition, like the offering of certain sort of gifts or trinkets or whatever, doesn’t placate indigenous peoples, and it doesn’t function in the way to pacify our resistance, you’ll always see the hammer come down.”

He says that force remains the primary way in which Canada reinforces its colonial policies.

“The Wet’suwet’en block, the breach of the blockade by the cops and the extraordinary force that they use, is just one example of that.”

Palmater sees Canada’s colonial playbook in action everywhere and marvels at the organization it requires to maintain and enact.

“Well, we know residential schools wasn’t a mistake… there’s a lot of thought, planning, processes that go into running a school that goes into designing it, that goes into creating the laws that make it mandatory to go to those schools and think of the coordination that’s involved,” she says.

“You’ve got the federal government, who’s ultimately responsible for these schools, coordinating with the different churches, coordinating with the RCMP to enforce to keep parents out to arrest parents, jail them if they try to get their kids, to make kids come back to these schools, to not act on abuses.

“And we know what the final solution was,” Palmater adds, referencing residential school architect Duncan Campbell Scott’s infamous quote from 1910. “It was to get rid of Indians. And how could you say that all of these kids dying is the final solution and not think that that was an intentional genocide?”

With files from Josh Grummett, Christopher Read, Rob Smith, Kenneth Jackson and John Murray.