By Josh Grummett

APTN Investigates

Two former employees of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada say the department is nowhere near meeting its mandate of hiring a 50 per cent Aboriginal workforce.

Jonah Keeshig and Fred McGregor also told APTN Investigates that the mandate itself is a taboo topic at AANDC headquarters.

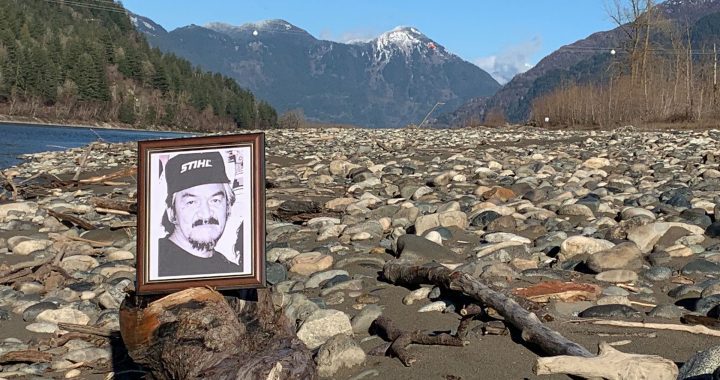

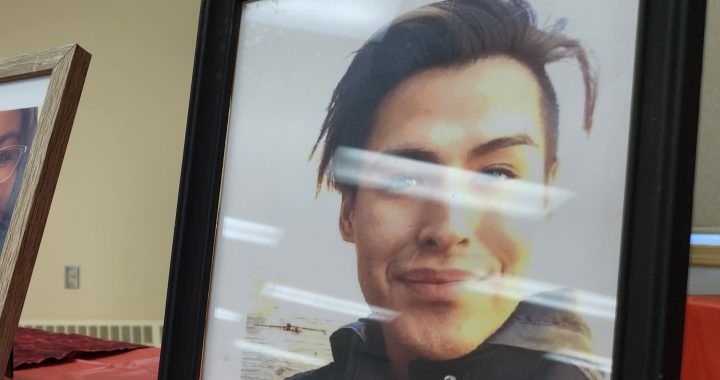

Jonah Keeshig worked for Aboriginal Affairs as a registration officer in its Adoptions office, helping adopted children get their Indian status. He was part of a group of 16 Indigenous employees hired as part of a recruitment drive in 2008. All 16 were dismissed in 2011, mere weeks before they would have become permanent employees. At the time of their dismissal they were working to address a backlog in the processing of status card applications.

“When we were first hired, it was for one year,” says Keeshig. “They kept us on for another year. When it came down to the end of that, they said, ‘No, no, we’re still in a backlog, we still need you.’ So they hired us again.

“Now if they keep doing that past the three-year mark, you’re permanent,” he continued. “You ain’t going anywhere. And basically, that’s what we were all looking for. We all had families.”

Keeshig was an executive member of CANE, the Committee for Advancing Native Employment, when he was employed by AANDC. He says that the process of their termination started with some internal testing that took place a few months before they were fired.

“They wanted to do an examination,” says Keeshig, “If we passed that exam, then we could continue on working.”

He says the process was announced in December of 2010, and the exams took place in January and February of 2011. All members of the group of 16 Indigenous employees who would later be terminated took the exams.

“We were led to believe by management that they would keep us,” Keeshig said. “Even regardless of the exams that were going on, they always kept saying, ‘Don’t worry about it, it’s all good, just write the exam and you’re going to become permanent.'”

Keeshig believes that his marks may have had nothing to do with his dismissal. During a meeting with HR in which he challenged his results, Keeshig says “the marker from HR said, ‘Well you answered everything right. It just wasn’t what we were looking for.'”

That comment, along with allegations of cheating and favouritism that were beginning to circulate, was the writing on the wall for Keeshig.

“That’s when we started suspecting that we were not going to be extended,” he says.

Shortly before their term ended in March of 2011, they were extended for just one month, and dismissed at the end of April. None of the 16 term employees had reached the point where they would be considered a permanent employee.

As APTN Investigates revealed in its November 29, 2013 episode, those 16 employees were replaced by 75 employees from Service Canada who had no experience with Indian status card registration and did not have the proper security clearance to access the Indian Registry System, causing already existing delays in status card processing to skyrocket. (Watch the full episode here.)

Fred McGregor was Keeshig’s co-worker, employed in AANDC’s Entitlements office, which handled the bulk of status card applications. He says that when he was there, the mandate to have a 50 per cent Aboriginal workforce was a taboo topic around the office.

“No one was listening to that,” says McGregor. “No one wanted to hear that. No one in the public service. When we were out, that was brought up after the fact. But when [the 16 Indigenous term employees were still employed], nobody wanted to discuss that.”

McGregor worries that there will be little to no accountability for the disastrous decision to let him and his co-workers go, saying that “everyone in this situation has either retired or left. It’s no skin off their back.”

Eight of the employees launched a grievance with AANDC over their dismissal. According to e-mails provided by Keeshig, the Union of National Employees dropped the grievance in late 2012, stating that they had found no wrongdoing.

AANDC’s commitment to work towards hiring a 50 per cent Aboriginal work force dates back to November 22, 1996. On that day, the department signed a letter of understanding with the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs stating that AANDC “has a long term objective of having a majority of DIAND employees with Aboriginal ancestry” and “will make every reasonable effort to reach… a 50 per cent hiring share for Aboriginal peoples.”

Keeshig says that today, AANDC is nowhere near that total.

“With all of us [the group of 16 Indigenous term employees] hired, we were at 29 or 30 per cent,” says Keeshig. “And then, when they let us go, I don’t know what it went down to.”

When asked about the number of Indigenous employees at the department, as well as Keeshig and McGregor’s claims, AANDC did not respond directly. Instead, they later released a short statement saying that due to privacy laws, they are unable to divulge employees’ personal information, and that government firing policies were respected.

While AANDC did affirm that they are committed to hiring indigenous employees to “increase their representation”, they did not release the number of current Indigenous employees, and their statement made no mention of their letter of understanding with the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs.