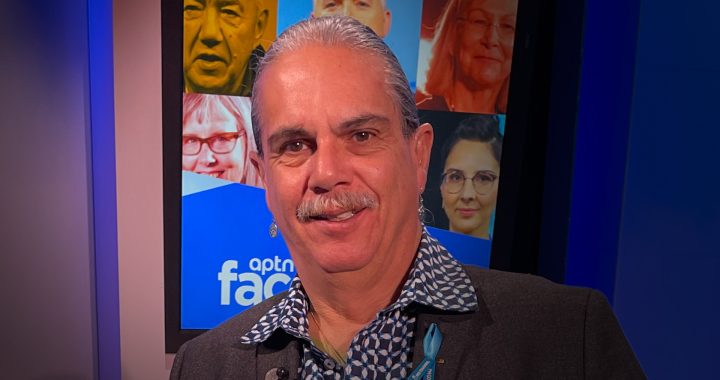

Cree filmmaker Tasha Hubbard wishes she never had to make the documentary nîpawistamâsowin: We Will Stand, which follows the family of Colten Boushie, the young man who died from a gunshot to the back of his head in August 2016 after entering the farm property of Gerald Stanley in Saskatchewan.

“I felt compelled to make it,” says Hubbard of her award winning 2019 documentary after just finishing her first feature film and intended on taking a break from work.

“When it happened, I was so struck by the suddenness of the violence, of the response by the RCMP, by the actions of the RCMP, by the horrible social media comments, some made by leadership, by people who are in leadership positions and I just thought this story has to be followed,” she tells Face to Face Host Dennis Ward.

Hubbard recalls hearing the news about Boushie’s death while driving with her son and nephew in the back seat.

She kept looking in the rear view mirror and wondering what kind of a world they were going to grow up in, especially with some people on social media celebrating the fact that a young Cree man had been killed.

Hubbard remembers sitting behind the Stanley family in the courtroom as the not guilty verdict came down.

“Indigenous people know that injustice is an everyday occurrence in the legal system, we know that,” says Hubbard. “We are repeatedly told ‘trust it, trust us’ and when you’re repeatedly told that, I think there is some part of us that have this last thread of hope. That maybe this time it’s going to be ok, trust the system.

“And when that decision came down, that thread was ripped out.”

Hubbard believes the justice system is working just as it was meant to work.

“It’s not meant for us. It’s not meant to protect Indigenous people. It’s not meant to give us the respect that we’re due. It’s constantly the opposite,” says Hubbard.

Shortly after Stanley’s not guilty verdict, the family met with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and members of his cabinet.

They met again earlier this year in February, shortly before the start of the global pandemic.

“We mentioned, ‘you said there was going to be real action taken. You made commitments to this family that this was the beginning and conversations we’re going to continue,’” says Hubbard.

Hubbard believes everyone should be disappointed that no changes have been made to the justice system or within policing.

Earlier this year, the RCMP Civilian Complaints Commission handed over a report on the Mountie’s investigation into the death of Boushie and recommendations to the commissioner of the RCMP.

The report has not been made public and has not been shared with the family.

The family continues to push for an Inquiry.

“How many deaths have happened for Indigenous people and people of colour for wellness checks? Family members calling because they’re worried about their loved one and they come and kill them,” says Hubbard.

“The head of the RCMP and the head of the Alberta detachment deny there’s systemic racism or say they don’t know what that means and that’s not acceptable. That wasn’t acceptable in 1873, it’s not acceptable now.”

Hubbard has previously tackled racism within policing in her award winning, 2004 documentary Two Worlds Colliding.

The film is a look at the infamous freezing deaths in Saskatoon, also known as starlight tours.

Two Worlds Colliding examines the case of Darrell Night who was dumped by police in a barren field on the outskirts of Saskatoon.

Night survived but others have not.

The film was being shot at the same time as the inquest into the death of Neil Stonechild was taking place.

Hubbard made the film out of a concern over how the story would be told.

“The mainstream media has a lot to atone for when it comes to telling Indigenous stories. And I wanted to have a space for these families to speak,” says Hubbard.

In the film, an investigator points out it would take a generation before there would be significant changes in policing in Canada.

Hubbard believes police have become very concerned about their public image and are trying to market themselves as having made changes while trying to maintain the power they have.

“My concern is the increased militarization of police and seeing their budgets and their purchase of tanks and body armour and all of these that haven’t made a difference in there being safety in the community.

“It’s actually made it the other way where it’s been unsafe for people because there’s this and there’s an attitude that comes with that militarization.”

Hubbard, who is from Peepeekisis First Nation in Treaty 4 territory has made four films to date, all have received awards, including the 2017 documentary Birth of a Family.

The film is about the reunion of four First Nations siblings separated as part of the Sixties Scoop.

Hubbard herself was adopted into a farm family and grew up in rural Saskatchewan.

She’s witnessed a lot of changes in the film sector.

“It’s been pretty incredible seeing the rise in numbers of Indigenous filmmakers from when I first started until now,” she says. “For every story that I have been able to tell, I know that there are so many more like that that also deserve that time and that space.”