Jolynn Winter, left, with Kanina Sue Turtle days before Kanina's death. Jolynn would also die by suicide about two months later. Facebook photo.

Just over a year after Kanina Sue Turtle died by suicide in a Sioux Lookout foster home, the regional coroner said in his final report on her death that it didn’t appear anything could have stopped it from happening.

“In this case, the final stress does appear to have been an interpersonal conflict. It is not clear what interventions would have made a difference,” wrote Dr. Michael Wilson Nov. 27, 2017.

Wilson wrote this about 21 days after he requested that Kanina’s crisis intervention counsellor in Sioux Lookout send him all of her records.

APTN News has those records and they make up a large part of this story, one that APTN has been investigating since February.

Kanina died on Oct. 29, 2016 inside a foster home owned and operated by Tikinagan Child and Family Services.

The records show missed appointments with Kanina’s counsellor before she died and how the counsellor struggled to talk to people at Tikinagan to find out why.

APTN has already reported that Kanina was “chronically suicidal”, had hundreds of new self-inflicted cuts all over her body, made multiple hospital visits before her death and had the bruised outline of a noose around her neck that was clearly visible in a Facebook live video posted on her account.

She also filmed her death on her iPod.

That video showed Kanina was left alone for 45 minutes before anyone came to check on her. She had already been motionless for 40 minutes.

But the records from Kanina’s counsellor at the Nodin Child and Family Intervention Services, detail portions of the child’s last days alive that have gone unreported until now – much like the coroner’s report into her death that family just received in August despite multiple meetings with the coroner’s office.

And still, after all this time, her parents, Barbara and Clarence Suggashie, don’t know why she was left alone the day she died.

They didn’t get answers from a report released this week into Kanina’s death and 11 other children that perished in child welfare. That report, organized the by Ontario’s chief coroner, Dirk Huyer, found no one person was to blame for any of the deaths but the system as a whole had failed each and every one of the kids. Eight of them were Indigenous.

As APTN reported Thursday, Kanina’s parents are suing Tikinagan for $5.9 million alleging her death was preventable. They also hope it will finally give them the answers they have been looking for.

‘They don’t give a lot of information about the place she stays’

Violet Tuesday was Kanina’s counsellor but had difficulty reaching her in the days before she died.

Tuesday’s case notes show missed appointments and unreturned calls by Tikinagan when she tried to find out why.

Information pulled from the records for this story are published exactly how they were written by Violet Tuesday, including the misspelling of Kanina’s name.

“I called Intake of Tik to let her know that Kenina never called or her escort (house sitter) they were to call me today for her apt.,” wrote Tuesday Oct. 24, 2017, five days before Kanina died. “The Intake was going to find out where she is/also her worker is Ashley.

No one from Tikinagan called back.

The next day Kanina was a no show, again.

“Intake never called today or the sitter of the place where Kenina stays. They don’t give a lot of information about the place she stays. Waiting for them to call,” wrote Tuesday Oct. 25, 2017, four days before Kanina died.

The next day Tuesday spoke to a Tikinagan worker at the hospital but didn’t recognize the girl sitting with the worker.

It was Kanina.

“I saw her sitting in the waiting room with a girl (Tik worker) but I didn’t know it was her because she had her long hair down with red streaks,” wrote Tuesday Oct. 26, 2017, three days before Kanina died.

“I saw her briefly. She has been cutting again. I asked her if shew as suicidal/stated no. I told her I was sorry for not recognizing her. The last time I saw her she really want to go home/her father wanted her to come home. I think she was frustrated/lonely.”

They made an appointment for the following day.

Again, Kanina didn’t show up.

Tuesday called Tikinagan twice before Kanina’s worker called her back.

“I called Tik Intake to ask about Kenina. I was told to call Ashley. I told her she doesn’t pick up her phone. Intake called Ashley. Ashley did call back,” Tuesday wrote Oct. 27, 2017, two days before Kanina died.

Ashley explained that Kanina was not doing well and that she had taken off with a friend.

The friend was Jolynn Winter, Kanina’s girlfriend.

“Her friend was only 12 years old/suicidal together,” wrote Tuesday. “They got caught kissing each other. She stated she told Kenina she could get charged doing this to 12 year old.”

In a video posted on Kanina’s Facebook both of the girls are giggling that day behind a building and kiss a couple times. APTN has reviewed that video and at one point a bruised outline of a noose is clearly visible across Kanina’s neck.

Tuesday asked why Kanina didn’t show up for her appointment.

“She is very angry/upset at everyone. She doesn’t want to come Nodin,” wrote Tuesday. “Ashley stated they are going to send her into treatment.”

Tuesday said to bring Kanina for a counselling session the next day at 10 a.m.

At 1:15 p.m. Tuesday called Tikinagan to see where Kanina was.

Tikinagan told Tuesday they were taking Kanina to Dryden, about an hour from Sioux Lookout.

“I asked her how she was doing now. She described Kenina as calmed down/talking now. She was going to bring her in for a few mins to see me but I told her to bring her Monday at 10 am for counseling,” wrote Tuesday on Oct. 28, 2017, one day before Kanina died.

That same day Kanina tried to kill herself in a wooded area.

She appears panicked and looks over her shoulder as though she thinks someone is looking for her.

“I don’t know what to do anymore,” Turtle says in the short video. “I’m sorry for what … umm… I’m going to do.”

Kanina was found dead the next day.

After her death, Nodin’s files were reviewed.

“The assigned counselor had considerable difficulty contacting the client as indicated on 4 case notes. One of those notes explains how the (Tikinagan) home staff took her to Dryden rather than come in for her session,” the review states.

Love and Death

APTN reported earlier this year that Kanina and Jolynn Winter were close but left out details of their relationship.

They had met while in a Tikinagan treatment centre in Cat Lake several weeks before Kanina died.

APTN reported that Tikinagan suspected both were suicidal and had separated them in the days before Kanina’s death. That included turning off the Wifi at the home Kanina was being kept at.

This infuriated her. The day she died she ran away from the home and the Ontario Provincial Police apprehended Kanina and returned her to the home according the coroner’s records.

Jolynn was hospitalized after Kanina’s death for over two weeks. Her grandmother told APTN she had tried to kill herself.

In January 2017, Jolynn did die by suicide.

Both of their deaths were part of a so-called expert panel review of 12 deaths of kids in child protective services.

But the panel didn’t dig into individual cases looking to hold any person or agency accountable, rather it reviewed files looking for systemic problems.

Overall, it found the child welfare system was failing children.

The panel highlighted the relationship between Jolynn and Kanina.

“In the weeks and days prior to (Kanina’s) death, the two were together on a number of occasions. Although this relationship is referred to in various documents, there was no evidence of supportive discussions around Kanina’s sexual identity,” the panel wrote. “Additionally, it appears that staff indicated to her that she could be arrested for engaging in a sexual relationship with Jolynn, as a result of Jolynn’s age.

“While this is accurate from a legal perspective, this position does not demonstrate responsiveness or recognition of the needs Kanina was endeavouring to meet.”

When Jolynn was hospitalized after Kanina’s death she spoke to staff about their relationship.

“There were no records suggesting that Jolynn’s sexual identity was ever discussed with her while in hospital or by staff of other organizations including (Tikinagan),” the panel wrote.

There were no mental health treatment beds available when the hospital discharged Jolynn. So, Tikinagan sent her home to her father on an “extended visit” in Wapekaka First Nation. Her grandmother previously told APTN it was the first time she had ever been home.

“A safety plan was agreed to by the hospital, (Tikinagan,, the family and Jolynn. There was, however, no evidence of active therapeutic intervention during the seven weeks she was in her father’s home,” the panel wrote.

“At the age of 12, Jolynn died by suicide in her father’s home. Kanina’s death by suicide is felt to have been an influencing factor in Jolynn’s suicide.”

The panel said Kanina left a note for Jolynn and her various members of her family but Kanina’s mother said they have never seen any letters.

Suicide Pact

After the deaths of Kanina and Jolynn another person close to them was struggling.

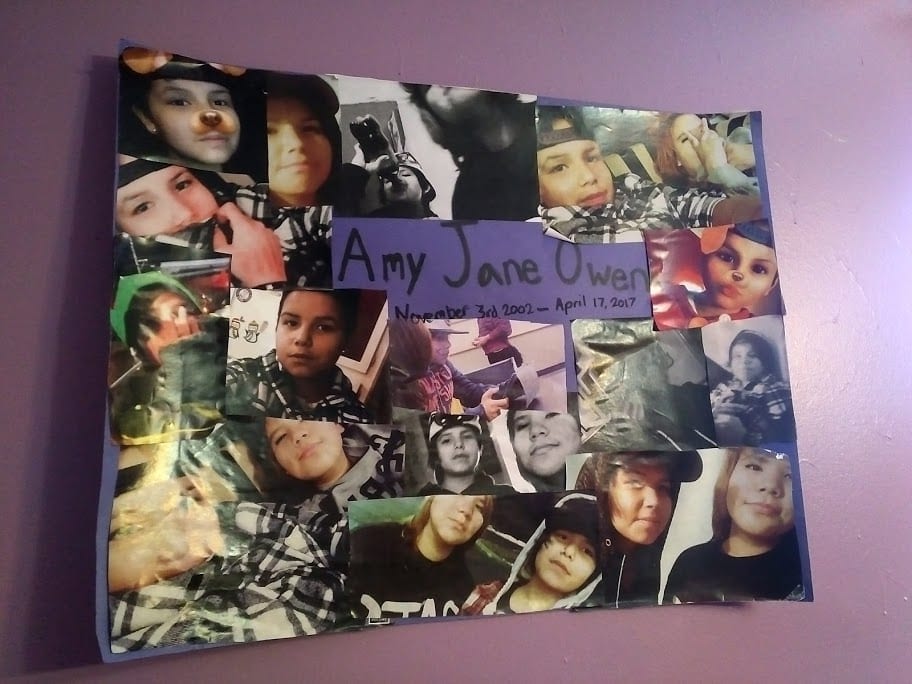

Her name was Amy Owen, who was also from Poplar Hill but living in groups homes in the Ottawa area.

She was transferred to Prescott, Ont. just a few days before Kanina died.

The owner of the home told APTN Tikinagan said she was in a suicide pact. The panel also found that Amy was in a suicide pact with two other youths but didn’t name them.

APTN previously connected Amy’s death to Jolynn and Kanina.

Amy was transferred to an Ottawa group home after an altercation with staff at the Prescott home. The owner also thought she would be safer in Ottawa as Amy kept trying to run to nearby railway tracks.

It was during that transfer that she learned of Jolynn’s death.

After repeated visits to the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario Amy died by suicide in the Ottawa group home.

She was supposed to be placed under 24-hour supervision but, according to the coroner’s report into her death, a specialized home for that type of care was at capacity.

All three girls were under the care of Tikinagan and each one was suspected of being suicidal before they died.

In the Suggashie lawsuit against Tikinagan, it alleges that the Indigenous child welfare agency is incapable of caring for Indigenous kids.

“(Tikinagan) failed to adequately monitor Kanina,” the claim alleges. “Its employees or agents had no or improper training, qualifications, education and experience to supervise and/or assist Indigenous children suffering from mental health issues, including Kanina.”

Tikinagan has not responded to requests from APTN to address the lawsuit.

APTN asked Ontario’s chief coroner if he agreed with the conclusion reached by his regional coroner that it didn’t appear anything could have prevented Kanina’s death.

“The Expert Panel has provided their perspective about the system of care available to the 12 youth who were subject to their review. They have identified many concerns about the system and provided a number of recommendations to inform change,” wrote Huyer in an email.

APTN also asked if his office should have been subjected to the panel review.

“We do not provide care to youth–unfortunately we are only involved after a death has occurred,” he said.