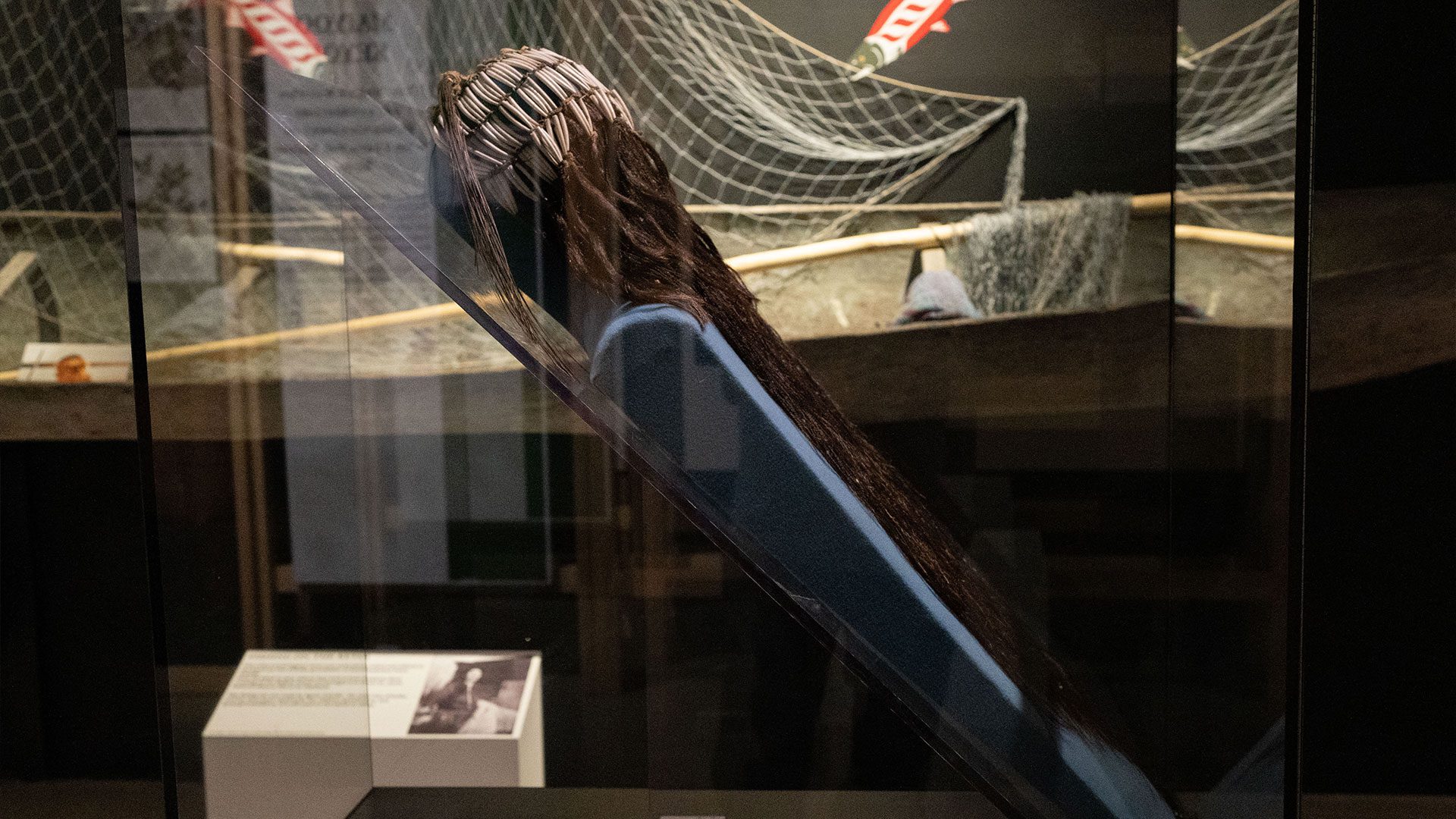

The Royal Ontario Museum has repatriated a 200-year-old Susk’uz chief’s headdress to descendants in northern B.C.

The Susk’uz headdress belongs to the Keyohwudachun or Chief George A’huille, whose family holds a Keyoh or traditional land near Fort St. James in northern B.C.

“We went down to the museum in Toronto; the first time we got to see it, it was amazing,“ said Petra A’huille, who holds the title of Keyohwhaduchun and is the great-great-granddaughter of George A’Huille.

The family worked with B.C. Museums, Canadian Heritage and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission on its return.

In 2022, the museum repatriated the headdress to the Maiyoo Keyoh Society, which is now on display close to home at the Exploration Place in Prince George.

“It makes you feel so good that you have something that your ancestors left you,” A’huille said.

A’huille said the headdress is an important cultural artifact as it is connected to Dakelh hereditary title, land and governance system.

Jim Munroe, the president of the Maiyoo Keyoh Society, a group that was established to protect ancestral territory, said the pre-contact practices still happen today.

“The title of Keyohwudachun, which George A’huille was a Keyohwudachun, is passed down from generation to generation,” he said.

Munroe said around 145 years ago, the headdress made it into the hands of Father Adrien Morice, the first resident priest near the territory.

It was around the time at the beginning of the federal government’s ban on potlach.

“When he gave it to Father Morice, then Father Morice transported or had it transported to Ontario,’ he said.

The group only found out about the whereabouts of the headdress five years ago.

Munroe said despite many of Canada’s colonial practices meant to destroy their culture, they still have their family territory connected to the headdress.

“We still have our family territory, but through the Indian act, we were confined in a lot of ways to the reserve at Fort St. James,” he shared.

Munroe and A’huille’s children are also pleased to have their cultural belongings back.

Their daughter Antastazia Munroe talked about the beauty of the headdress.

“It’s a direct connection to my ancestors; the construction of it is through dentalium shells, noble women’s hair, its astounding to look at,” she said.